In my natural history classes, I emphasize the role that awareness and keen observation play in developing the skills of a naturalist. If we don’t see, hear, taste, smell, and touch the world around us with a refined palette, we miss out on all those rich, textured layers of intoxicating beauty, mystery, and intrigue that write the story of place.

Humans (at least the vast majority of us) are unique in that we are neither predator nor prey. Not relying on our senses to survive, we have to actively learn to be observant and curious lest they atrophy and we blunder along oblivious to what transpires in the more-than-human world. It doesn’t help that so many species rely on camouflage, making it much more difficult for even the most aware of us to detect them.

Where’s Waldo?

When teaching observation skills, I often use a series of “Where’s Waldo?” images I’ve taken to talk about the many different ways an animal can avoid detection. Each “Where’s Waldo?” image has some small beast obscured in a tangled tapestry of twigs, leaves, mud, and dappled light (album). When we see a chipmunk in the middle of the road, it’s pretty easy to spot with those black and white strikes down its back contrasting plainly against the asphalt backdrop. But put that same chippie in the context of crisscrossing honeysuckle branches and it becomes quite difficult to spot. And as much as it serves as a segue into the many forms camouflage can take, it also begins to develop a search image for wild things.

Types of camouflage

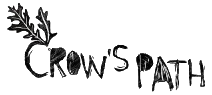

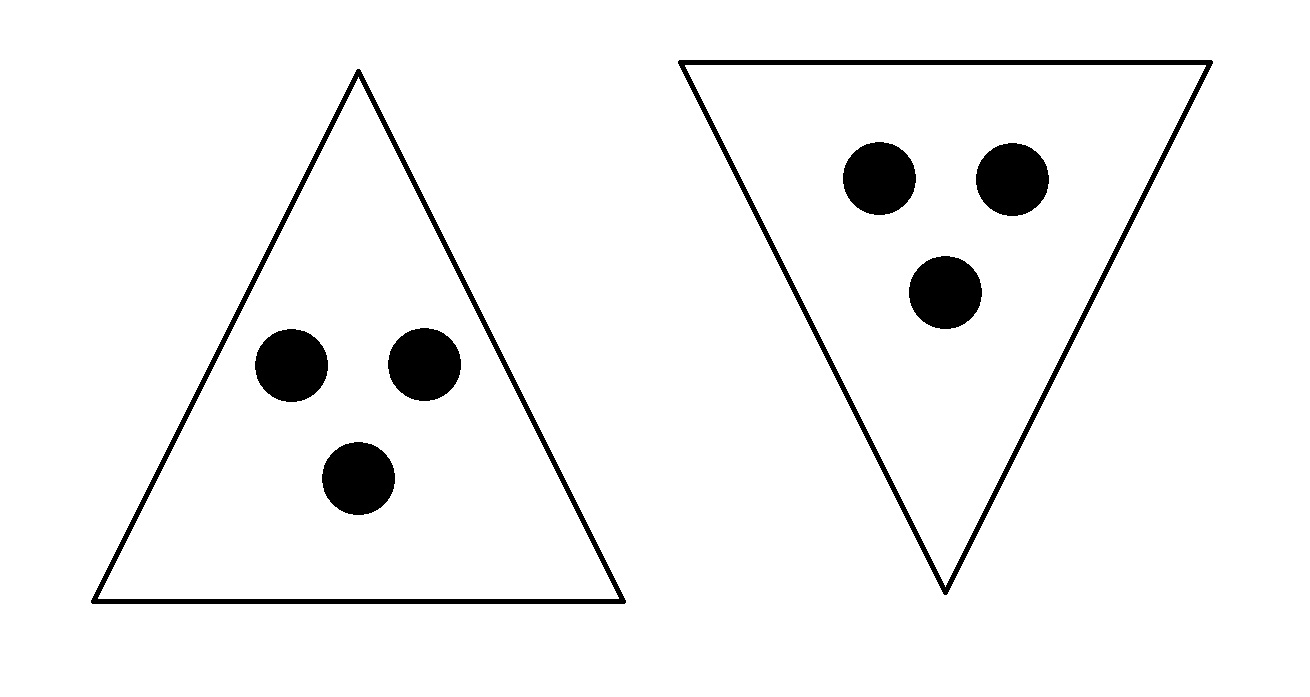

To understand camouflage, it’s best to start by describing how animals discern other animals from the rest of the world. For most vertebrates, it’s faces. We are captivated by things that appear to have eyes and a mouth. Babies prefer to look at an object with a face-like pattern over one that does not have a face-like pattern. They are also discern the top-heavy pattern of a human face. Give a baby two triangles with three dots arranged as in the image above, they will spend more time looking at the triangle with the triangle that mirrors the top heavy weight of a human face (bigger forehead than chin). Even fetuses respond to face-like patterns (source).

Because we generalize the pattern of an animal’s face (or body plan), whether friend, food, or foe, we map this pattern onto non-animal things like clouds, twigs (check out my series of Twiggies photos), or even cattail seed heads (from my Hermae series). From the perspective of the animal being detected, their ability to fly under the radar is largely based on their ability to disrupt a recognizable pattern or anatomical feature. But more on that next week…