An intro to gait patterns

Most tracking books emphasize the features of a clear print for identification, count the number of toes on the front and rear feet, look for claws, note the shape of the track, etc. Add it all up and presto, you know who made the track. But when you’re out in the field it can be pretty hard to come by that perfect print, particularly for older trails. Each gait (e.g. a walk, lope, trot, hop, bound, or gallop) leaves behind a distinctive pattern of tracks (see image below). And each family tends to have a preferred (or baseline) gait when traveling under normal conditions from point A to point B. Combining gait patterns with size can usual pinpoint the species without need for clear detail in the individual tracks (though a clear print can certainly confirm a hypothesis). Looking at gait patterns also reveals deeper clues about how an animal interacts with a dynamic environment inhabited by ferocious predators, delicious food, startling sounds, curious smells and other sensory inputs that demand the animal’s attention, even if for just a moment.

Baseline Gait

All animals can do all gaits (here’s a video of a beaver galloping). I first heard this maxim from Mike Kessler, and while it’s may be true, the morphology of a species narrows the range of gaits to a few preferred options. And again, each species has a baseline gait, the pattern of movement that’s most efficient for the animal to move from point A to point B. If your dog, for example, is going for a “walk” by itself, it’d happily trot down the sidewalk. You cat prefers to walk stealthily past the barn and out to the meadow, a squirrel bounds energetically from the base of one oak to the next, a fisher lopes through the hemlocks in search of a red squirrel, and so on. Knowing how to tell the different gaits apart and familiarizing yourself with the baseline gaits of different species will help you quickly identify a trail.

* Baseline gaits are not absolutes. Topography, substrate, size/sex of animal can all influence the baseline gait. Additionally, animals can have different baseline gaits for travel and hunting, so use this as a general guide.

Skip to Descriptions of the different gaits

walks | trots | lopes | bounds & hops | gallops

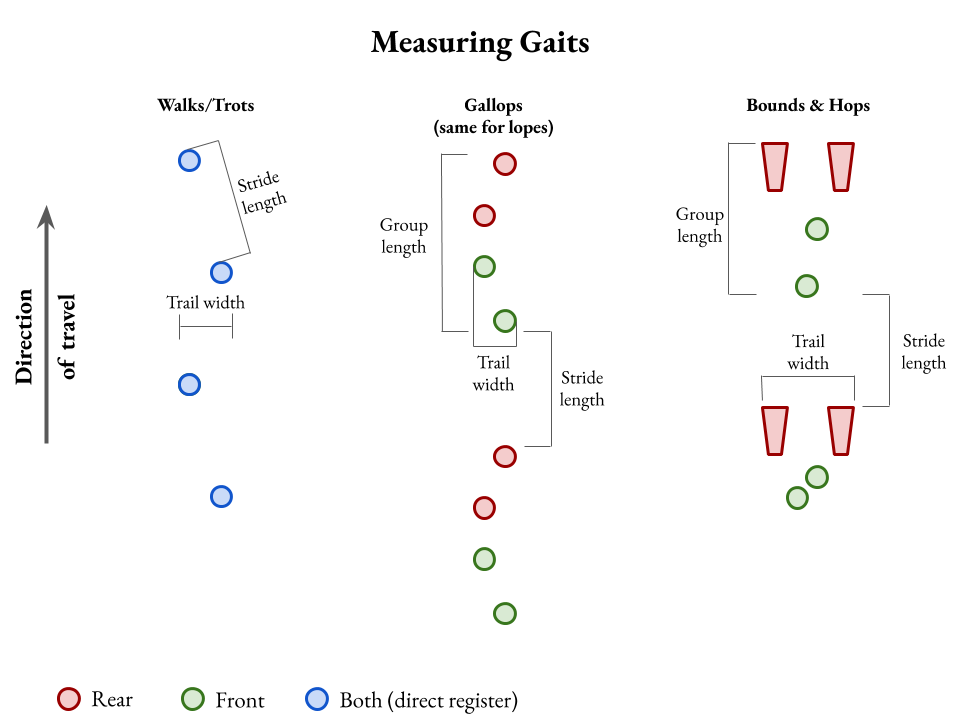

Measuring a gait

Because baseline gaits can be shared across families as well as within a family group (e.g. our canines – foxes, coyotes, and dogs – all trot in their baseline gait as do voles, shrews, and woodchucks), knowing how to measure a track can help you tease out the finer details to distinguish between different species (and sexes). There is considerable overlap in the method used by various authors to measure gaits, with a few small differences in each scheme. I follow Mark Elbroch’s methodology because his book is the most complete for cross-referencing measurements. Regardless of the scheme you choose, the most important element is that you’re consistent (note: be sure that when you reference a measurement you’re comparing the same type of measurement). The three key measurements

- Trail width: The width (or straddle) of a group of tracks measured perpendicular to the direction of travel at the widest point

- Group length: The distance between the trailing track and lead track of all four feet (only measured for hops, bounds, lopes and gallops)

- Stride length: The distance between the lead track of one group and the trailing track of the next group

Walking

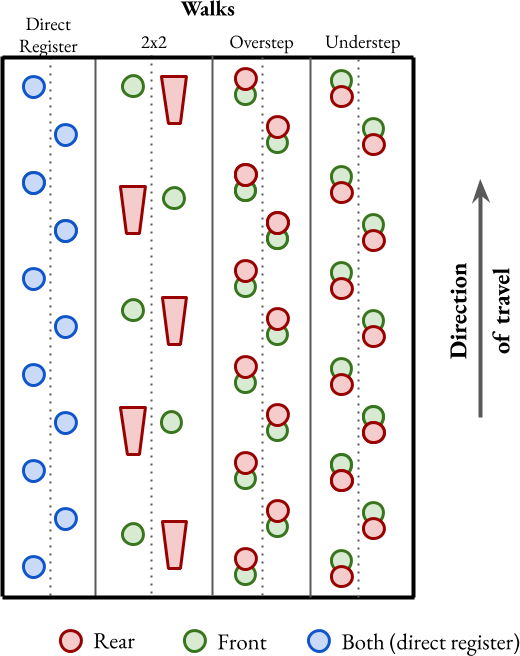

A walk is a slow gait. While walking, an animal’s body remains in contact with the ground at all times, and there are almost always 3 feet on the ground. Each foot moves independent of the other feet, and the four feet land in a steady beat without any pauses: Bop / Bop / Bop / Bop. Because walks are slow gaits, the animal has to use its feet rather than its momentum to stay upright. Imagine a cyclist cruising comfortably along the bike path, its 2 inline wheels cruising steadily along. Now compare this to the wobbly kid just learning how to ride a bike. Without training wheels, the little tyke struggles to stay upright as they teeter along. Here, our poor little kid is the walker, the speedy cyclist the trotter. In a walk, trail widths tend to be wider than in a trot, effectively acting as training wheels (or a tri-pod) to help stabilize the animal.

Variations

The faster an animal is walking the farther forward the rear foot will land relative to the front foot on the same side.

- Understep: In a slow walk, the animal will understep, with the rear foot landing behind the front. When the rear foot lands directly where the front foot was, it’s called a direct register.

Direct register: In a direct register walk – when the rear lands directly over the front track – you can also use the distance between the points (a Left-Right-Left or Right-Left-Right series) to get a rough estimate for the animal’s body length. The measurement is roughly equivalent to the distance from shoulder to rump.

- Overstep: As the animal speeds up, eventually its rear foot overtakes and lands past the front foot. In both direct register and overstep walks there is a brief moment when the animal has only two feet on the ground.

- 2×2: There’s another fast walk, called a 2×2 (used by raccoons), where the rear foot oversteps so far that it lands next to the front foot of the opposite side, almost as in a trot (video).

Walks outside of baseline

Animals may move out of their baseline and when something in their environment changes and the animal alters its behavior accordingly. A mountain lion in pursuit of a deer may switch to an extreme understep, a gray squirrel might walk while sneaking around looking for a place to surreptitiously bury a walnut, or a red fox slows into a walk as it approaches a scent marked stump.

Mammals that move in a baseline gait of a walk include:

- felines (e.g. bobcats, lynx, house cats)

- beaver

- porcupine

- muskrat

- bear

- opossum

- cervids (e.g. deer and moose)

- raccoon (a distinct 2×2 walk)

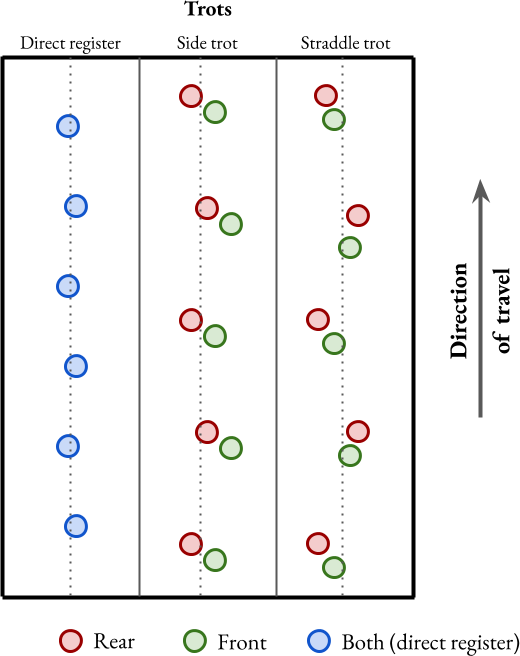

Trotting

When trotting, an animal has a bouncy, almost jaunty cadence: Boom / Boom / Boom / Boom. The diagonal limbs move in concert, so a left front foot pushes off and moves forward in sync the rear right foot. Just as these feet are about to land, the animal pushes off with the opposing pair of feet (the right front and left rear) and there’s a brief moment where the animal is airborne. Contrast this with the quieter walking stride where the animal remains on the ground at all times. Because the animal is moving faster, momentum helps keep the animal balanced and so trots tend to have narrower trail widths than walks.

Variations

As with walks, as an animal speeds up, the trot can take on different forms:

- Direct register: The rear foot lands comes down and lands in the same spot as front foot, immediately after the animal lifts up the front foot. As the animal slows it can move into an understep trot, similar to the understep walk (see above).

- Overstep trots: As an animal speeds up, it can transition into an overstep trot. But overstep trots create a problem as the animal’s rear foot moves past its planted front foot it would knock into it. There are a couple ways around this.

- Straddle trot: In straddle trots, the animal widens the straddle of the hind feet and keeps its front feet always within the straddle of the rear feet.

- Side trot: My dog does the side trot all the time as we’re heading out into the woods. It’s like his rear end can’t contain itself and is moving faster than his front half. With nowhere to go, his butt slides out to side trying to pass his front half. In side trots, the rear feet land to the sides of the front feet.

Animals that move in a baseline gait of a trot include:

- woodchucks

- shrews

- voles

- canines (e.g. dogs, coyotes, foxes)

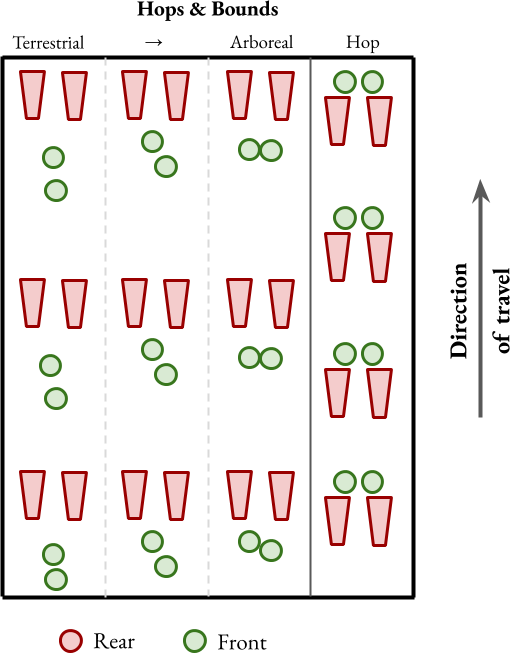

Hopping & Bounding

Hopping and bounding are similar movement patterns, and their differences in appearance more reflect a difference in speed than of mechanics. In both gaits, the animal uses its rear feet to propel itself forward, leaping energetically through the air, catching its fall with its smaller front feet. Animals that hop or bound as their baseline gait (e.g. squirrels, rabbits) tend to have much larger hind feet than front feet (these animals at rest also tend to have their weight resting on their rear feet.

- Hop: the front feet come down and land, usually side by side. The rear feet land shortly after just behind the front feet. The animal is firmly planted with all four feet on the ground before taking its next stride. This is a slower gait than a bound and is analogous to the understep walk or trot.

- Bound: the front feet come down first, landing briefly, while the rear feet straddle the front feet as they come forward and past them. As the rear feet are about to hit the ground at the same time, the front feet lift off the ground and the animal is airborne. The rear feet land and then push off, springing the animal up into the air where it is airborne for a second time.

Bounds have a large stride length relative to group length. For both gaits the rear feet land at the same time (Boom), while the front feet can land either at the same time (bop) or slightly offset (bop-bop), given the hop or bound the following rhythm: bop-Boom / bop-Boom or bop-bop-Boom / bop-bop-Boom

Offset front feet

Species who are ecologically more tied to running around in the trees (e.g. gray squirrels) tend to land more with their front feet side by side while animals that split their time between the trees and ground (e.g red squirrels) land with their front feet more offset. Ground dwellers like rabbits and hares have a significant offset between the two front feet (the group of rabbit tracks looks somewhat like a podracer from Star Wars). See the image above for a closer look at 67this pattern.

Animals that move in a baseline gait of a hop include:

- rabbits

- snowshoe hares

Animals that move in a baseline gait of a bound include:

- chipmunks

- red squirrels

- gray squirrels

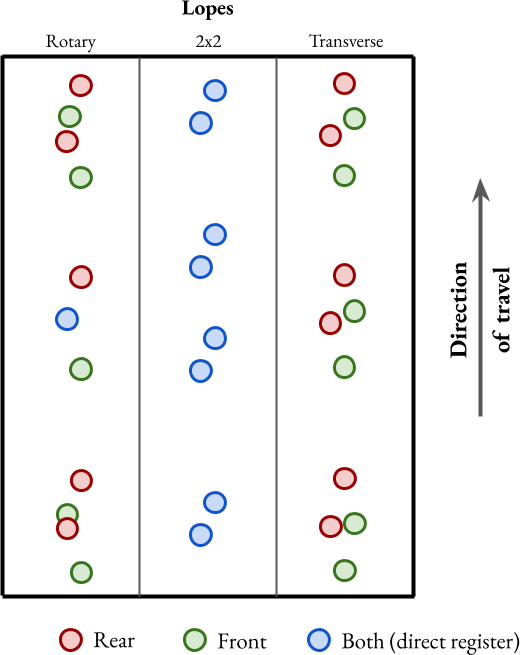

Loping

As an animal speeds up beyond a trot it increasingly uses its hind legs to propel itself forward. In a trot, the opposing legs (e.g. rear right and front left) move in concert, but in lopes the rear legs begin to move more as a unit and the front legs as a separate unit. The footfalls, however, are still independent of one another, giving the gait’s cadence a rhythm as follows: bop-bop – boom-boom / bop-bop – boom-boom (bops are the front feet, booms are the rear feet). A group for loping gaits always appear as a front – rear – front – rear sequence.

- Rotary: in rotary lopes, the leading front foot is the opposite from the leading rear foot (e.g. the left front and right rear are leading) giving the group a C-shape. Often the lead front and trailing rear overlap, which gives the group the appearance of just 3 tracks (Elbroch calls this a 3×4 lope).

- 2×2: essentially this is a direct register lope. The front feet land slightly offset from one another and pick up just as the rear feet drop to the ground, landing in the same spot where the front feet just were.

- Transverse: the transverse lope is like an overstep 2×2 lope. The lead foot is on the same side for both the front and rear feet (e.g. the left front and left rear are leading).

Animals that move in a baseline gait of a lope include:

- mustelids

- weasels: 2×2, but also use rotary and transverse lopes

- mink: 2×2

- fishers

- male: rotary/transverse

- female: 2×2

- otter

- skunks

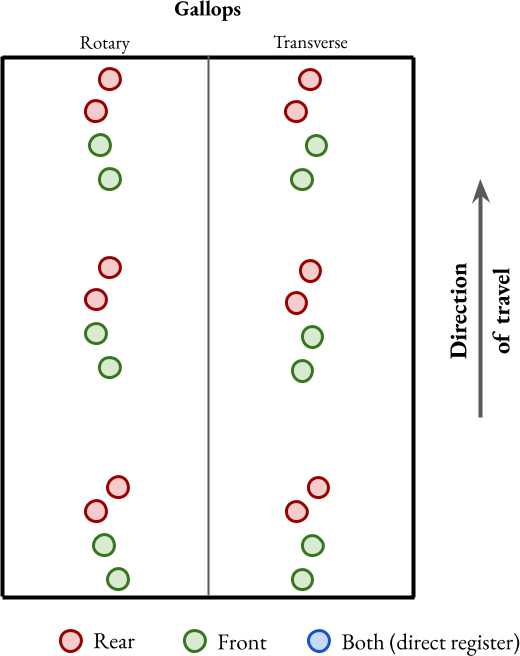

Galloping

Gallops are generally the fastest of the gait patterns, and very similar to lopes in appearance of the tracks and mechanics of the movements, except in a gallop there is a second point at which the animal’s body is airborne. In lopes, one front foot is still in contact with the ground when the first rear foot hits. In the faster gallop, the front feet land and then pick up off the ground before either of the rear feet touches, and the animal is briefly airborne . The rear feet land Boom – Boom and then push off propelling the animal forward, at which point the animal is airborne for a second time. The faster the gallop, the farther the rear feet land beyond the front feet. The tracks in the group go front-front-rear-rear (as opposed to front-rear-front-rear in a lope).

Gallops are not typically a baseline or traveling gait because they’re not as energy efficient (think about how long and far you’d be able to a sprinter vs jog). Gallops are used in quick bursts of energy, typically either to escape predators or capture prey.

Other Gaits

There are a few other gaits, but these mostly belong to bipeds and non-mammalian quadrupeds. One infrequent gait of mammalian quadrupeds is the Pepé Le Pew 4 legged hop, or pronk. In this gait all four feet land and leave the ground in concert. My dog, Boots McGovern, does this in deep snow and tall grass as he alternates between bounds, lopes, and gallops. It is an overly excited gait.

Resources

There are plenty of tracking books out there, a few great, many terrible. If you’re going to invest your time and energy into tracking you might as well invest in the great ones. The two tracking books that I’ve found invaluable are Mark Elboch’s Mammal Tracks & Sign and Paul Rezendes’ Tracking and the Art of Seeing. Beyond identification, tracking reveals the often illusive ecological and behavioral world of wild animals. To supplement your tracking knowledge, it’to understand the ecological context of the animals you’re tracking. To that end, I suggest the following books: Michael Rentz’ Natural History and John Whitaker’s Mammals of the Eastern United States. For inspiration, Tom Brown, Jr’s book The Tracker is unrivaled. The documentary The Great Dance: A hunter’s story follows San Bushmen as they hunt using ancient techniques, and is well worth a watch.

Direct register: In a direct register walk – when the rear lands directly over the front track – you can also use the distance between the points (a Left-Right-Left or Right-Left-Right series) to get a rough estimate for the animal’s body length. The measurement is roughly equivalent to the distance from shoulder to rump.

Direct register: In a direct register walk – when the rear lands directly over the front track – you can also use the distance between the points (a Left-Right-Left or Right-Left-Right series) to get a rough estimate for the animal’s body length. The measurement is roughly equivalent to the distance from shoulder to rump.