I’ll start this newsletter the way I started the last one: It’s been hot. Real hot. And while we’ve had a few warm days earlier in the season, this is the first real stretch of heat for the year. Record breaking heat. When the weather’s hot, it can be a real source of stress for organisms. Read on for why heat’s a problem and how plants solve the problem!

Why is heat so bad?

Feeling so worn out by that stretch of hot weather last week got me to wondering, just why is heat so problematic? Yeah we feel lethargic and uncomfortable when it starts to get hot out, but that’s just our internal sensors telling us that things are getting bad, symptoms of an underlying problem. I came up with a short list of problems living things face when they start to heat up:

- Heat denatures proteins (including enzymes), which are essential for every metabolic process. Proteins have optimal temperature ranges and can’t function outside of these ranges.

- The rate of evapotranspiration is quicker when it’s hot out (important for terrestrial organisms, not so much aquatic)

- Warm water holds less oxygen (important for aquatic organisms, not so much terrestrial)

And while it doesn’t apply to all organisms, I thought I’d just mention that temperature (not really “heat“) can also affect the development of young individuals. In amphibians, for example, temperature-dependent sex ratios often skew towards males with warmer temperatures (link).

Some solutions

Organisms exhibit all sorts of pathological symptoms as body temperature begins to rise. These symptoms are signals to the organism that it’s time to make some behavioral and physiological changes or suffer the consequences. These symptoms also act as control mechanisms that seek to cool the organism down. With humans, we got hot and we might sweat (your dog will pant, a turkey vulture poops on its legs), seek out shade, increase blood flow to extremities, drink more water, go swimming, etc. The end effect of these symptoms is that we stop doing whatever is making us too hot. And all of these many different solutions act in concert to maintain our ability to tolerate 90 degree heat.

Some solutions in plants

While plants might not be able to go swimming or seek out shade, they’re anything but passive organisms in their environment. And when the weather turns suddenly hot, plants have a few nifty tricks at their disposal to survive these short-term heat waves:

Nyctinastic movements

Many plants exhibit what are called nyctinastic movements, or movements of leaves that operate on circadian rhythms. Leaves droop at night and perk up during the day. Clusters of cells at the base of leaves (or leaflets, as in the black locust above), help control these movements. While it’s not always clear why plants let their leaves hang low at night (though nocturnal herbivores is leading the race: link). It appears that this ability can be co-opted by the plant during the day in extreme heat.Both my lupines and sorrels appear to fold and collapse their leaves during hot, dry spells.The primary function of doing this during the day is to minimize the surface area of the plant exposed to the sun, thus reducing both the temperature of the leaf and the rate of evapotranspiration.

Black locust is another nyctinastic species, but with a twist. It’s leaves droop at night, but during the middle of the day they clamshell up and then drop again during the afternoon, like one big (like my favorite Calatrava building: link). The vertical orientation of the leaves is controlled by pulvini, the swollen bases of the leaflets (see image above). Again, by folded up its leaves, black locust minimizes the leaf surface area exposed to the sun.

Incipient wilting

The ability to prevent water loss is certainly an adaptation for dealing with heat. Being able to withstand wilting and recover is helpful for plants that lack skills in the first skill. Incipient wilting refers to the amount of wilting a plant can withstand and still recover to 100% health. And not all plants are equally suited to the job. It’s hard not to get too technical here, but I’ll try. As water evaporates out of the plant, turgor pressure (essentially the force of water filling up each plant cell and putting pressure outward on the cell wall) keeps a plant cells rigid and the plant as a whole upright. If a plant loses water in a drought, turgor pressure drops and the leaf can no longer hold itself up. This is why vegetables become flaccid in your refrigerator as they slowly lose water.

If a plant wilts too much then cells can dry out and eventually die (due to plasmolysis). When a leaf begins wilting, it effectively does that same as folding up/down its leaves to reduce the surface area exposed to the sun. This decreases the surface area of the leave and also creates a microhabitat for the stomata (see below) on the underside of leaves. These together reduce the rate of water loss. If the plant can wait out the heat suspended in this incipient wilting state, it can rebound once the heat breaks and the rain falls. While there’s not a ton of research on this, the adaptive role of wilting in tropical plants for tolerating heat stress has been shown (link).

Close stomata

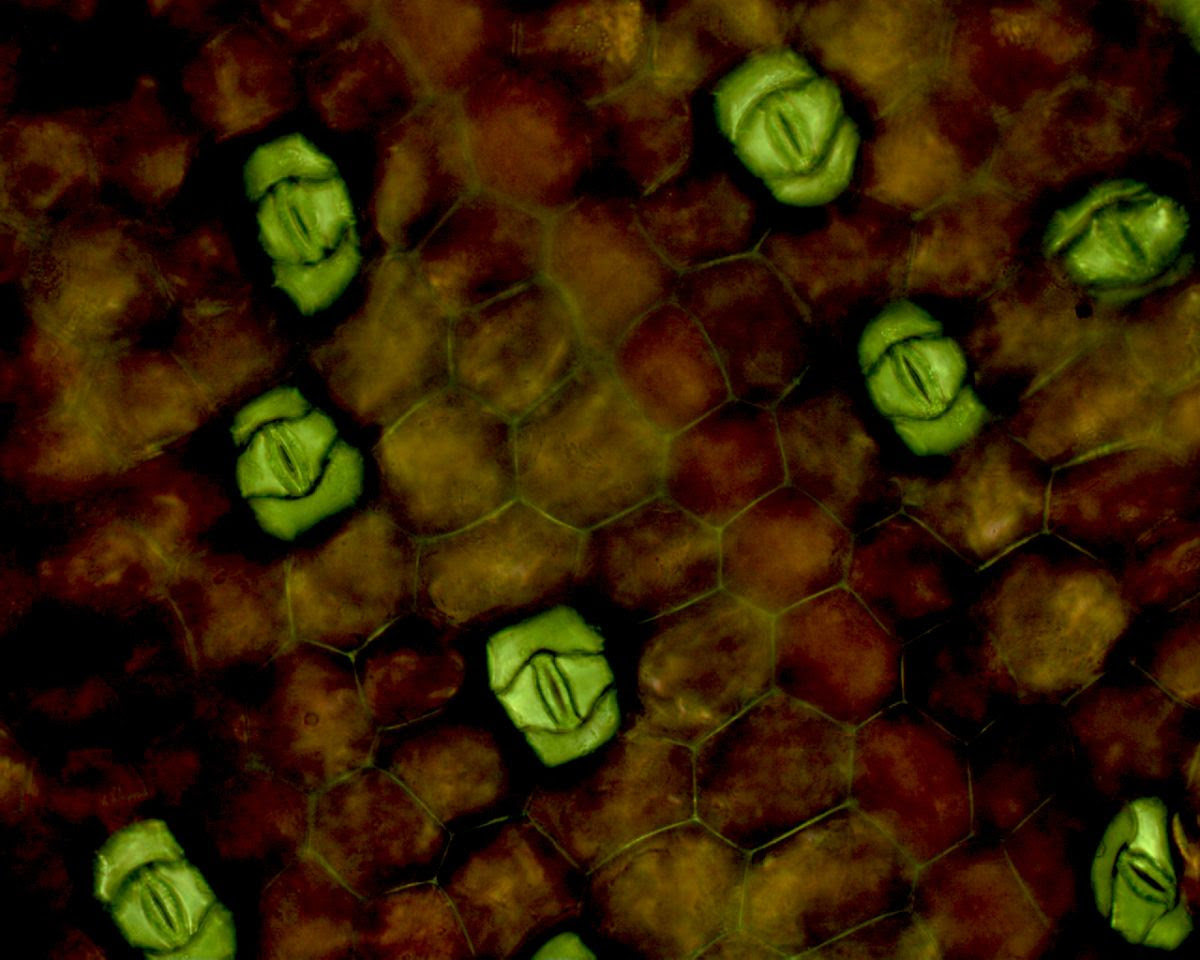

Because water loss can be such a big problem (and this is true not just during a heat wave – about 90-95% of water taken up by the roots is lost via evapotranspiration in the leaves), having a mechanism to slow this loss would be great. Water is lost through the stomata, tiny pores on the surface of the leave that allow for the uptake of CO2. These pores are flanked by a pair of guard cells that expand and contract to either open or close the hole, respectively. When temperatures rise, particularly when conditions are dry, the guard cells collapse and close up the stomata (sing. stoma).

Other solutions

There are other longer term solutions to dealing with heat that I haven’t covered here, like thick waxy cuticles, CAM and C4 photosynthetic pathways, erect stems (e.g. in cacti) to avoid direct sunlight, etc. Many of these solutions have evolved many different times, indicating that there are a limited number of good ideas for solving the same problem.