Before the heavier snow fell yesterday afternoon, we had a nice dusting of snow that recorded much of the evening and early morning mammal activity. The temperature was hovering around freezing, which made for some excellent impressions in the snow. Just outside my door it was skunk, rabbit, red and gray squirrel, gray fox, and mice. My daughter and I spent a bit of time looking at tracks, and it inspired me to do a deeper dive into tracking for the newsletter. So along the trail we go…

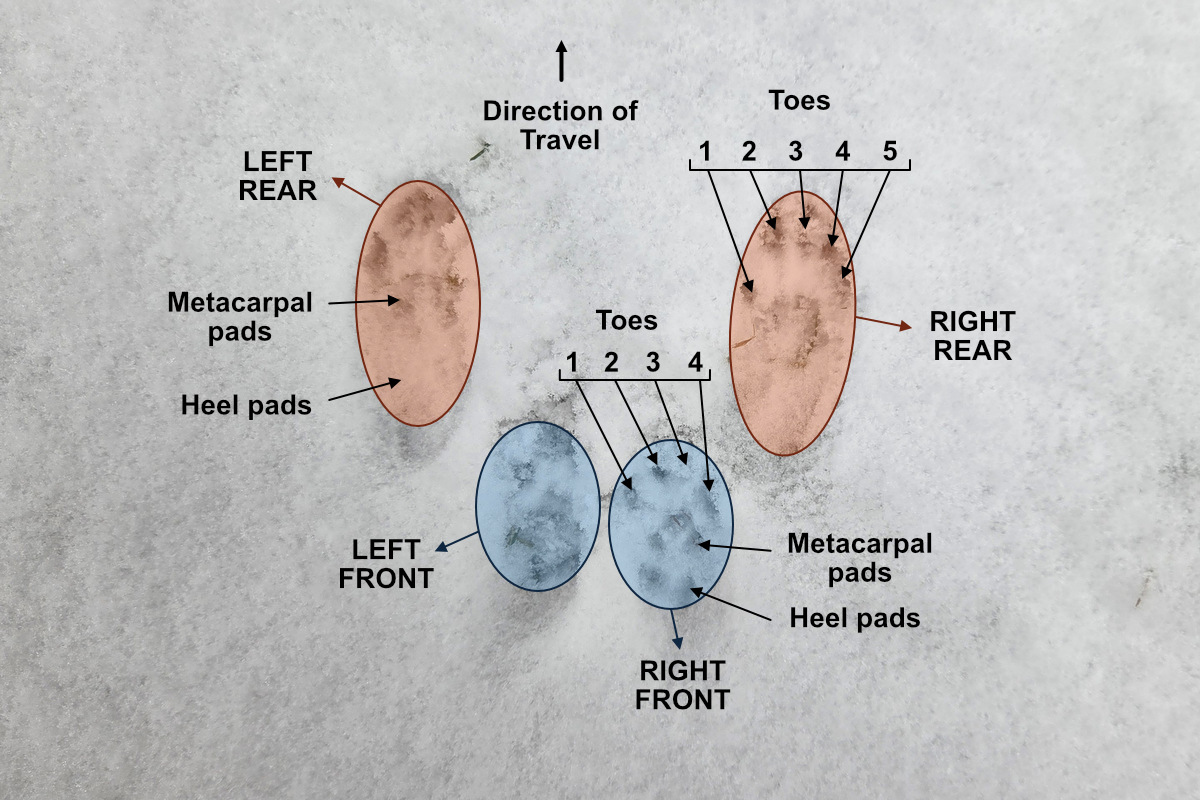

Before scrolling down, take a look at the image of the group of tracks below.

Where to start

Where did your attention go first? Were you counting toes? Describing the shape of the tracks? Looking for claws? Imagining how this animal was moving when it made those tracks?

It’s hard to know where to start when you approach an animal’s trail. The good thing is that there’s no right place to start. I used to spend most of my time looking at individual tracks before I started getting better at reading gait patterns, and now that’s where much of my focus goes. Either way, I find it incredibly helpful to add a splash of color to the otherwise monochrome canvas of a snowy landscape.

Take another look at the group of tracks, this time with colors and labels. What new information/questions pop out.

We can clearly see four different foot impressions, the two in the lead and outside (in orange) are significantly larger than the two trailing tracks in the middle (in blue). Relative size of the front and hind feet is important as well. A large discrepancy is a good indication that the animal uses its front feet in a very different way from its rear feet, like humans, squirrels, beavers, and raccoons and contrasted with dogs and shrews.

You might also notice that in both the rear and the front pairs of tracks, the feet land side-by-side rather than offset from one another. Another important detail, this one for telling the hoppers/bounders apart (we’ll cover this more when we look at gaits).

Because the tracks are so clear, we can count the number of toes: four on the smaller front feet, five on the hind feet, a pattern consistent for rodents. The tracks even show clear impressions of the metacarpal and heel pads. This tells us a fair amount about how the animal moves.

- Animals that are digitigrade, like your dog or cat, walk on their toes (digits), and so we only see metacarpal and toe pads in their tracks, not heel pads.

- This animal is plantigrade, landing on the flat of its foot and so we also see the heel pads. While the individual heel pads on the hind feet are difficult to see on this species (gray squirrel) because of their furry heels, we can still see the long wedge-shaped impression from the heel.

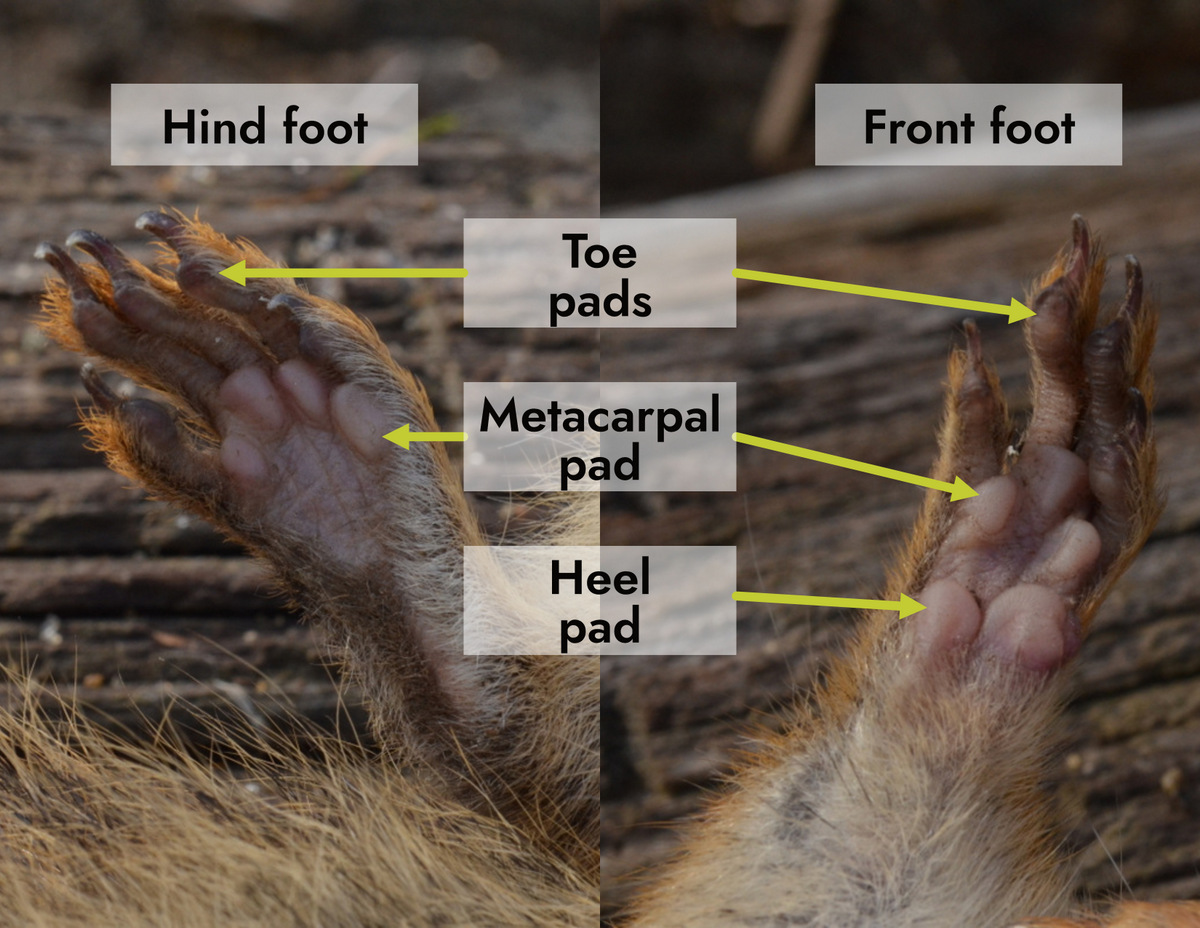

Real feet make tracks

I found that looking at animal feet improved my tracking skills tremendously. Look at the image below and compare against the tracks in the images above. While the tracks above are from a gray squirrel, their feet are quite similar to red squirrel feet, which I’ve labeled below. Both are arboreal and the well developed pads on metacarpal and heel pads on the front feet help catch branches when leaping from limb to limb. Having this visual aid brings tracks to life. In the next newsletter we’ll look at a few more feet and groups of tracks before stringing these together into longer trails.