In the last couple of posts, we’ve looked at static prints from domestic dogs and gray squirrels. While the track itself might be a frozen moment, it is the remnant of a dynamic moment, a point in a long line of impressions left in the wake of the animal as it walked, trotted, loped, bounded from location to location. Here we put our animals into motion, focusing first on how to determine which way the animal is moving.

Which way did it go?

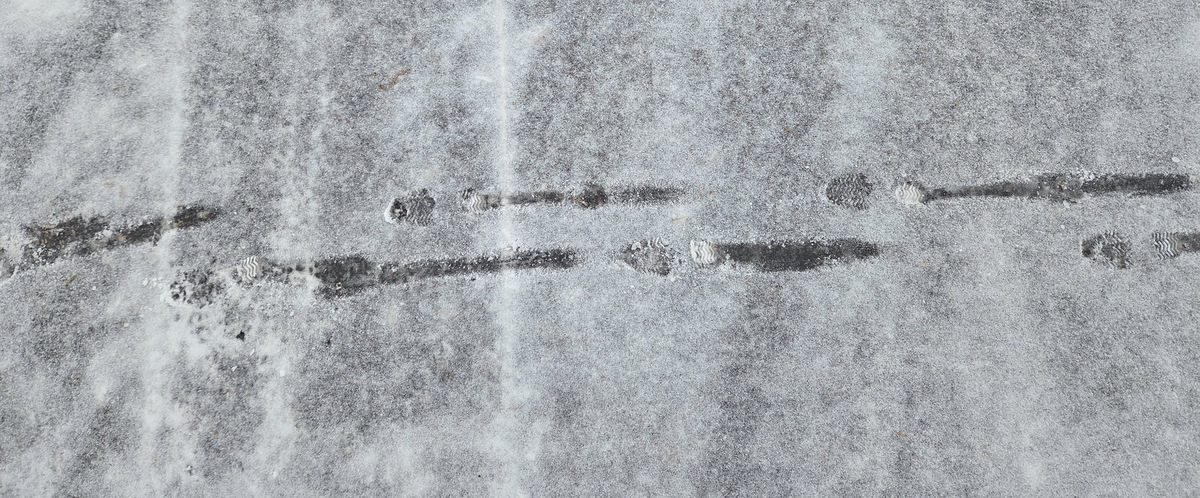

When we have a clear track with claws, toes, and heel pads, it’s rather easy to tell which way an animal is moving. But in fluffy snow or on older, weathered tracks that lack detail, as in the tracks above, we need other data points to tell direction.

The above image shows two groups (a group is a set of all four feet) of tracks from a red squirrel from two different trails. The trails were made in deep snow and there aren’t any clear details from the feet, so it’s a bit trickier to determine which direction the squirrel is traveling. Look again at the tracks in the image below (I ramped up the contrast), and some details start to emerge on both the leading and trail edge of the groups.

Now we can see a clear asymmetry to each group. In the group on the bottom, there are two lines coming out from the center of the group to the right and a rough snow “blasting” out from the track to the left.

Slow-motion replay

Watching videos of animals in motion starts to make sense of how tracks get that asymmetrical look to their topography. In the video below, Boots is galloping with great enthusiasm through deeper snow. It all happens in the blink of an eye (the real time between each “gallop” in the video is less than 1 second). But when we slow it down, we can see how Boots’ body interacts with the snow.

While you watch the video, pay attention to the following details:

- The rhythm of foot fall patterns (each foot lands somewhat independently of one another: Boom-Boom-Boom-Boom)

- Which feet drag as they enter the snow to create the troughs

- How snow blasts forward as the feet leave the ground

The lead-in trough

First, as the feet come down to land in the snow, particularly the rear feet, they drag over the surface before punching down into the snow. This leaves a smooth trough leading into the track. This is common in deeper snow and on faster gaits where there’s more horizontal movement. And sometimes it’s the front feet that drag, sometimes the rear. It also happens in tired animals, like my daughter who was lazily shuffling on our way home after a long walk. Here she was leaning back on her feet so her heel left prominent troughs leading in to the track. In the squirrel track at the top, the two lines are from the rear feet coming down to land.

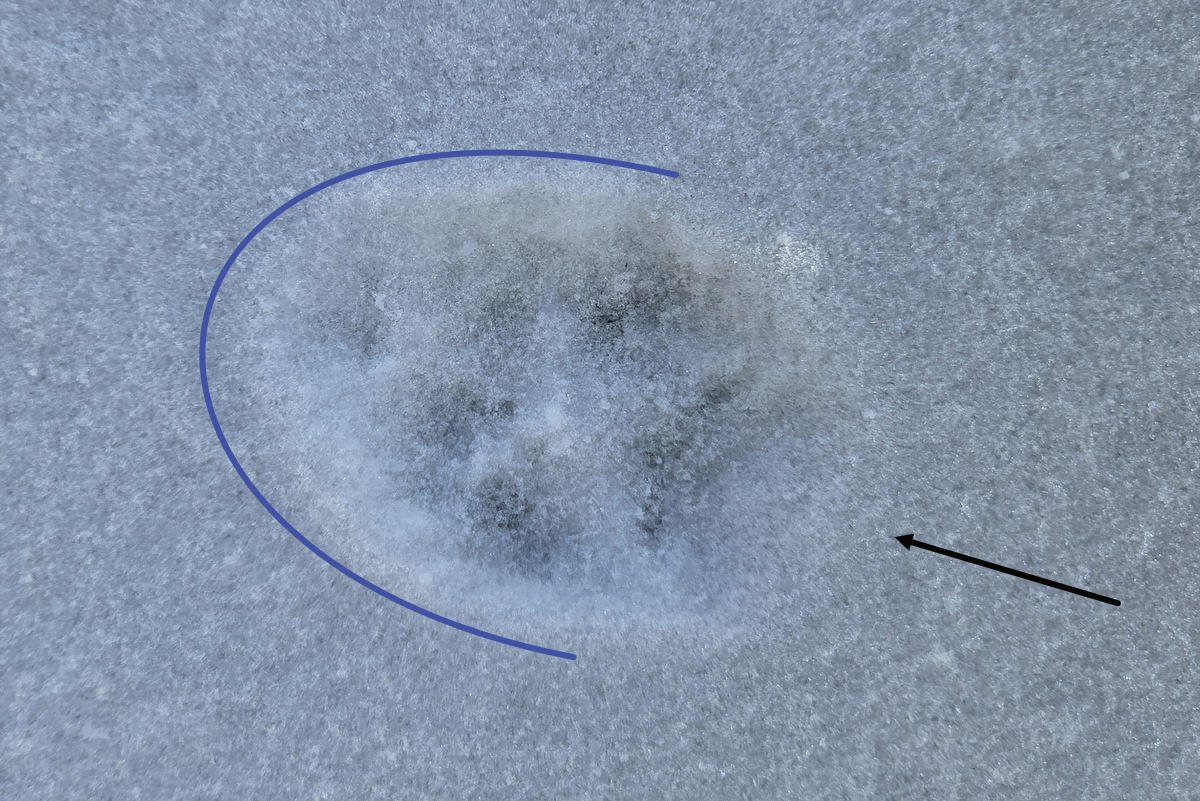

The blast-out mound

Back to the video, Boots’ rear feet are only in contact with the ground for a brief moment before they explode upward, propelling his body forward and creating an explosive spray of rough snow at the leading edge. This movement also plows snow forward in front of the track creating a small mound, which can be seen when looking at the track from the side. The rough snow is rather quick to weather away, but even on older tracks, the mound, even if subtle, can still be seen. In the red fox track below (front foot), you can see a halo snow on the leading half of the track (highlighted by the blue line). The black line shows direction of travel.

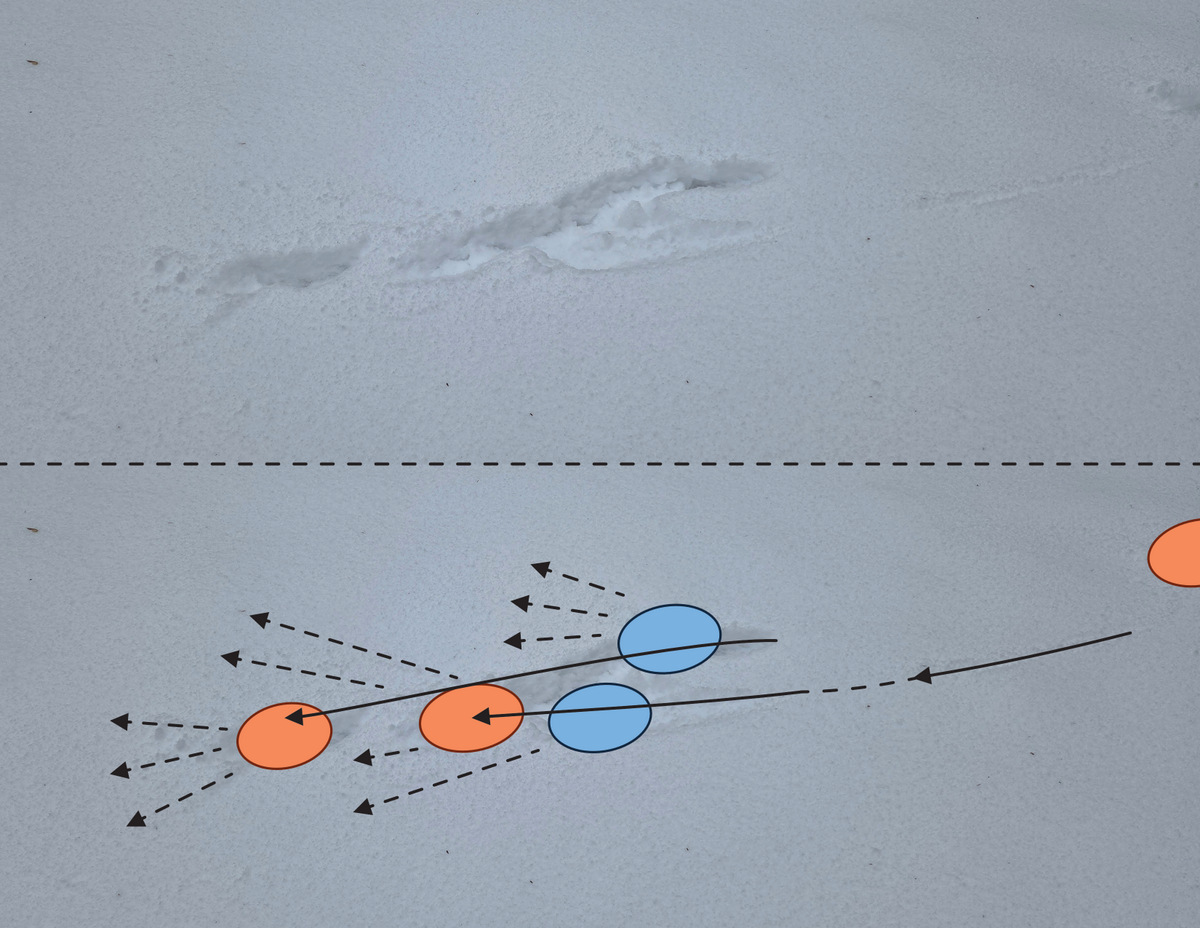

Below is a group of tracks from Boots’ gallop in the video. Below, I’ve highlighted the features of the tracks that give a clear sense of direction. Blue ovals are the front feet, orange are the rear feet.

Toe drags

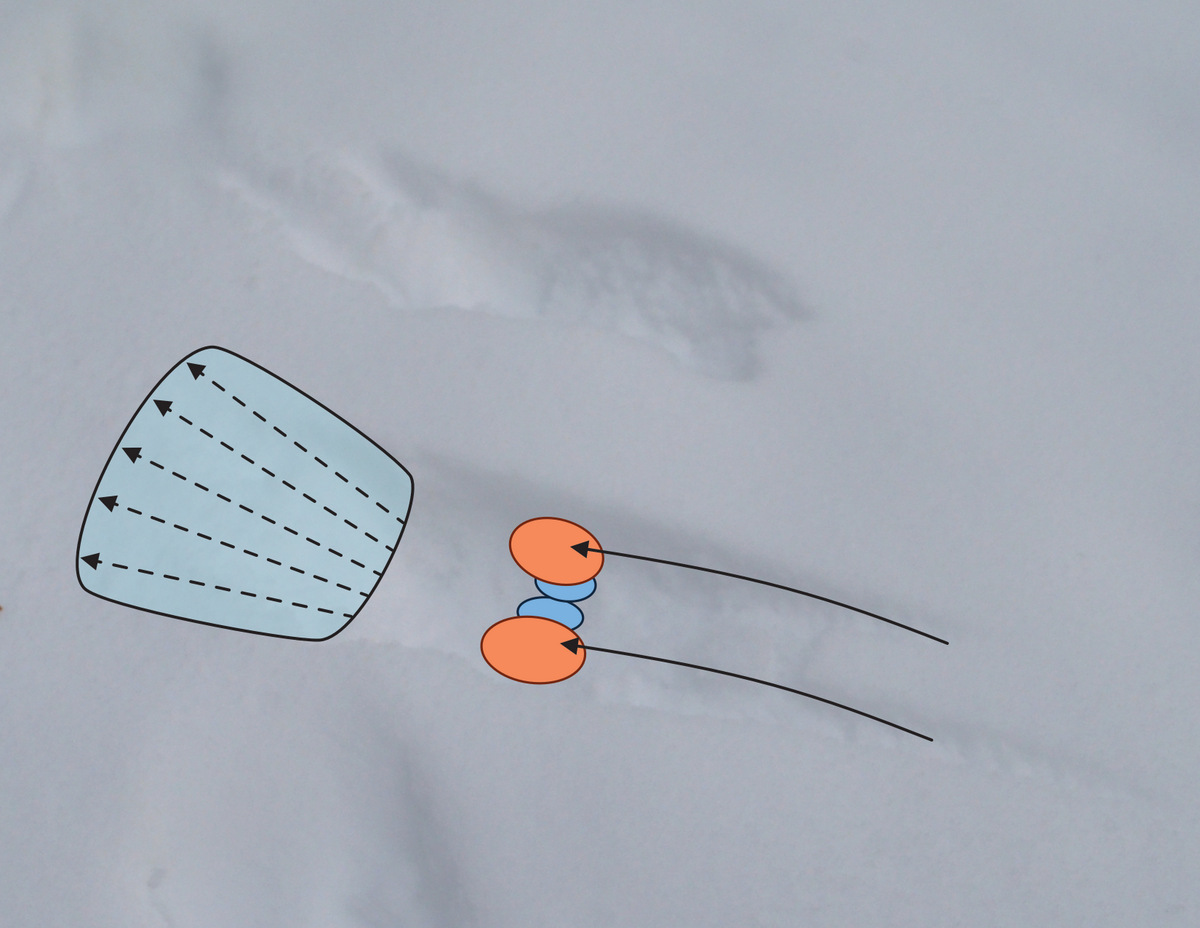

As a side note, not all drag marks are from the heel dragging across the snow. You often get toe or claw drag marks that lead out from the leading edge of tracks. These are particularly common on deer (these leave two parallel lines). Below is from Boots in a trot. Here it is the smaller hind foot that leaves the drag mark.

Back to the squirrel

Take another look at the image of the red squirrel tracks, now with labels. Solid arrows show the heel drag marks from the squirrel’s hind feet (orange ovals) as they come in to land. Dashed arrows show the “blast zone” as the front (blue ovals) and rear (orange ovals) feet spring out of the snow. While the unlabeled group at the top of the image lacks the heel drag furrows, it has a blast zone on the same side of the group, indicating both trails trails are traveling from right to left.

Another squirrel

The blast of snow can also be an indication of energy. If Boots is sitting and then bursts forward to chase a stick (or squirrel), he is more likely to leave larger blasts of snow. In the image below a gray squirrel was bounding on a very slipper ice surface and slipped. As the squirrel recovers and then springs forward, it leaves a dramatic explosion of snow on the leading edge. The second group in the series shows almost no sign of this.