My dog Boots is a wonderful field assistant, but this week he’s been an excellent teacher. Today we take a closer look at Boots’s body and feet to start to connect the shape of a track to the body of the animal that made the track.

Looking at tracks

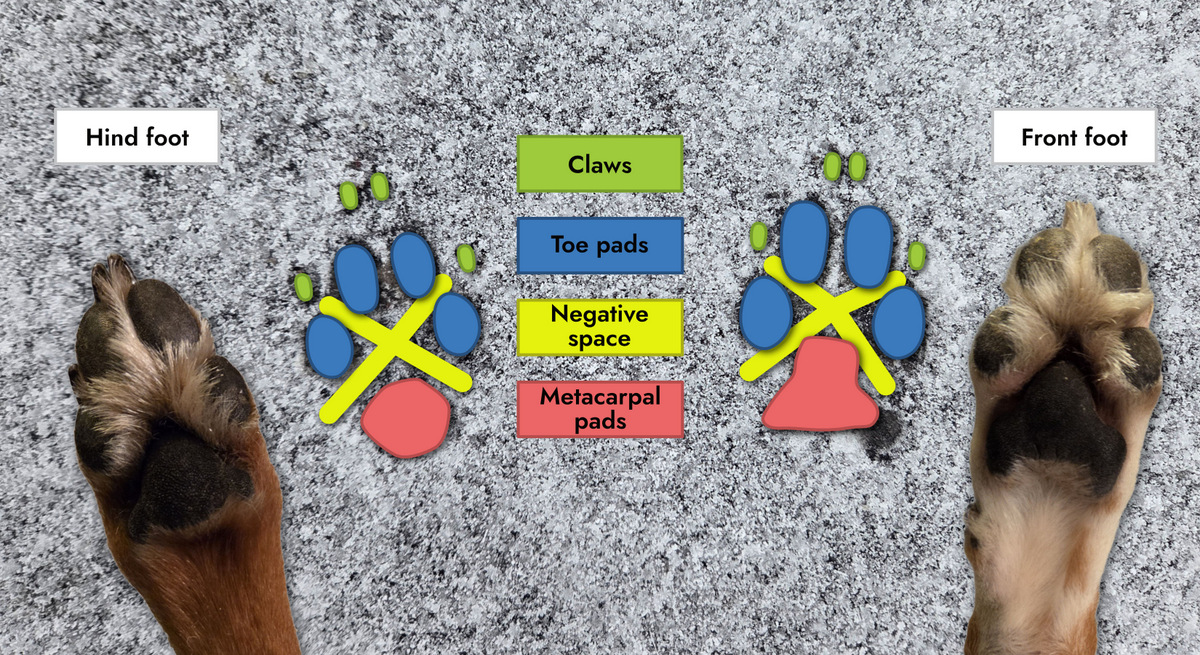

Take a minute to look at the two tracks in the above image. Same animal, but one a hind foot, the other a front. Some simple questions can help us draw out the subtle differences between the two tracks and guide us along a path towards both identification and interpretation:

- What’s the overall shape of the track (round, oval, triangular)?

- Is the track symmetrical?

- Are the front/rear tracks the same size?

- Are the shapes of the metacarpal (palm) and heel pads the same (note: these tracks don’t have heel pads)?

- Is the negative space (the space between the toes and metacarpal pad) the same shape/thickness?

- Do the claws show? If so, how close are they to the toes?

- How many toes on the front/rear feet?

As with the tracks I showed last week, I find it quite helpful to color in the different parts of the track to make the different features stand out. Here’s the same image, but with a color overlay. I also included the animal’s actual feet to show how this translates from foot to track.

Negative space

I’ve also labeled a new layer here: the negative space, or empty space between all those pads on the foot. On the animal’s foot, this looks like tufts of fur emerging from between the toes.

Sometimes the shape of the negative space can be diagnostic. In canines (foxes, coyotes, and domestic dogs), the negative space appears as an “X,” and a helpful mnemonic is that X marks the spot and Spot (the dog) marks the X. We’ll look at cat feet next which have a “C” shape to the negative space.

Foot-body connection

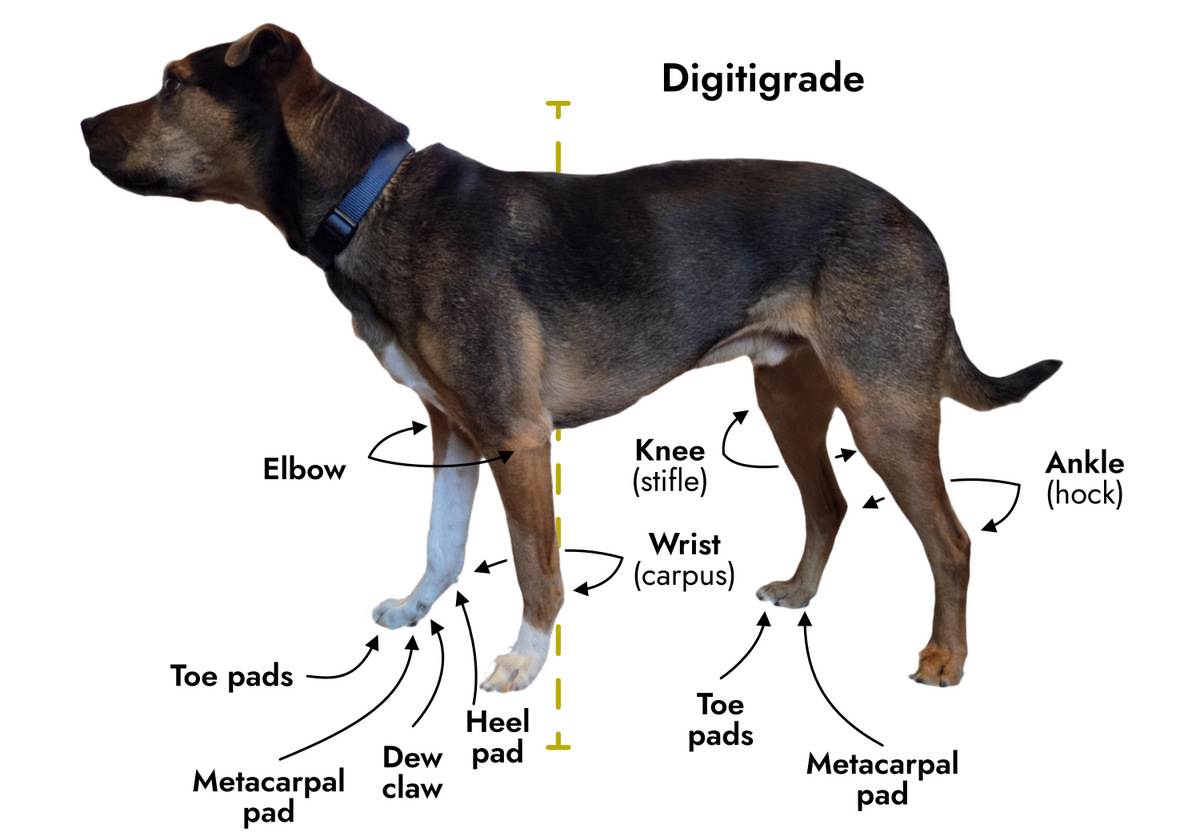

Tracks, of course, are made by feet, which, of course, are attached to an animal’s body. We can then, of course, use information from the track to infer details about how the animal stands/moves. We can also use information from watching an animal stand/move to understand why its tracks look the way they do.

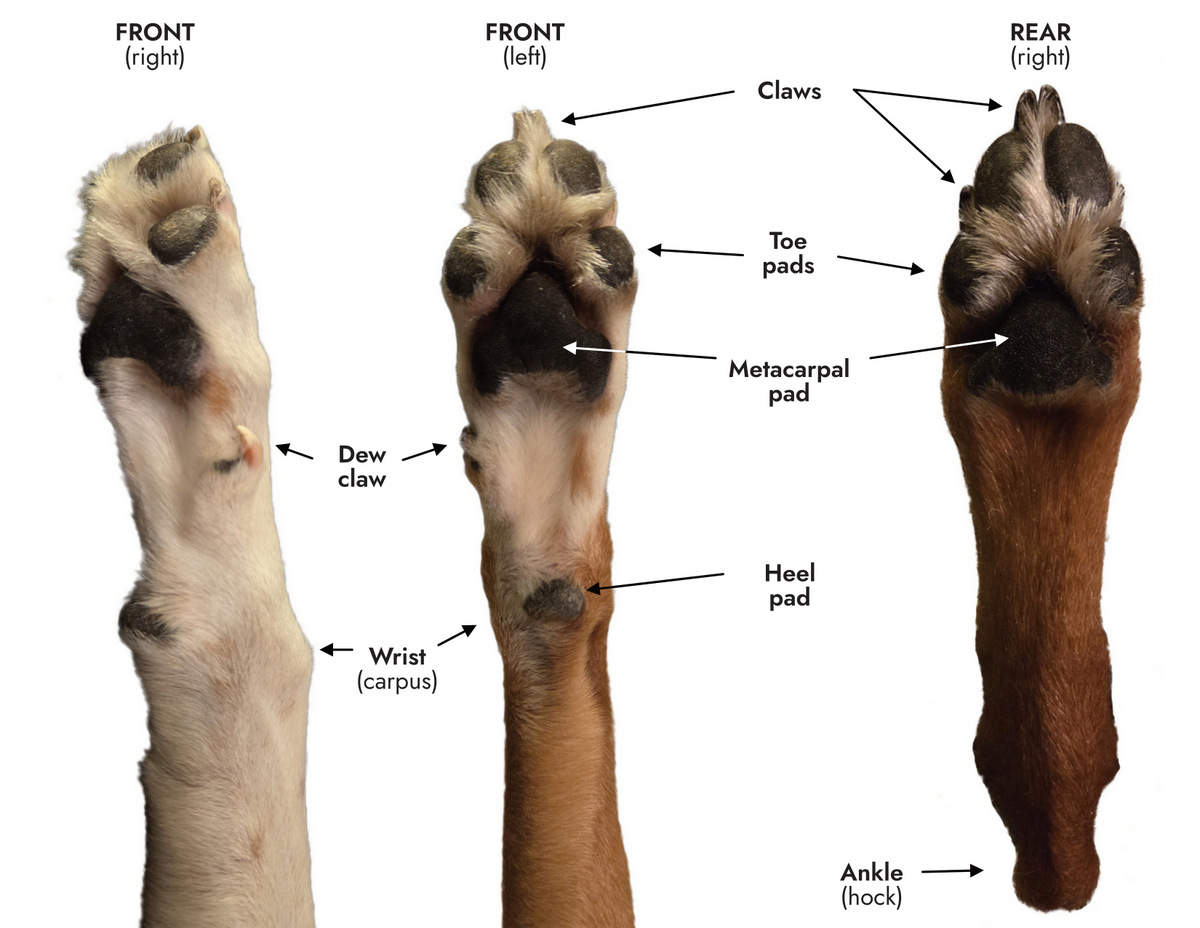

Take a lot at Boots in the image above and try to imagine how his posture influences the way he will leave tracks. We can see that he stands up on his toes, or digits, a posture called digitigrade. Here, the ankles and wrists of the animal are up off the ground and so the size of the track is relatively smaller than if the whole foot, heel and all, came in contact with the ground (called plantigrade). Look at the same image with labels that show the different joints on the leg.

Size of the feet

On the image above, I include a dashed yellow line roughly were the midpoint of his mass is located (I put a band under him and lifted him along different sections of his belly to find his balance point. All in the name of science). This line is significantly closer to the front feet, which means that his front feet are bearing the brunt of his weight.

If we return to the tracks from the top (shown again below), you’ll notice that the front foot (on the right) is the foot on the right is larger overall, with larger toe pads and a more robust metacarpal pad. As a general rule, animals have larger feet where the bulk of their weight is.