Welcome to the Wild Burlington Newsletter

The (mostly) weekly newsletter covers a wide range of natural history topics. You’ll discover the wild world around you with the help of professional naturalist, Teage O’Connor. So if you’re interested in tracking the changing seasons, connecting to your local landscape, and learning more than you ever wanted to know about twigs, then this is the newsletter for you!

Plus, you’ll also get nature quizzes, notes on upcoming events (like the Wild Burlington Lecture series), contests, and awareness activities that will engage you with the wild world. And it’s all delivered right to your inbox.

The newsletter is the perfect learning tool for naturalists of all abilities!

Digging the natural history content?

Please consider supporting Crow’s Path on Patreon.

Be sure to check the archives for back issues.

And shoot me an email if you have an idea for a future blog post, newsletter issue, or podcast episode!

The Wild Burlington Archives

You can also check out the blog for more natural history and the natural history section for field guides, essays, and other explorations of Vermont’s natural history.

Shrinkadees: What is a species?

When I was writing about chickadees last week, I kept thinking to myself: “What really is a chickadee?” Yes, I know what they look and sound like, but do our diminutive black-capped chickadees really have the same “black-capped chickadee-ness” as those slightly larger 19th century chickadees? And if our Vermont chickadees continue to shrink, at what point do they reach that critical morphological/genetic tipping point where we no longer classify them as Poecile atricapillus and instead mark them as some novel new species, perhaps P. minimus or P. anthropocenii?

Shrinkadees

This morning there was a chickadee in my backyard singing, “Hey Sweetie”. It had fluffed up its feathers, so it looked just slightly more intimidating than it would otherwise. Puffed or not, this was still a small bird, likely weighing about as much as a AAA battery. More than just being small relative to this naturalist, this early morning chickadee was about as small of a chickadee as you’ll find during the year.

Nesting smallmouth bass

I finally got back in the water for some early summer snorkeling. The surface of the lake was rather murky from all the pine pollen that's in the air right now, but the water was relatively clear below and so visibility was somewhat decent. And now that the water's above 60º, the smallmouth bass have all come up for the spawn and so I got to spend some time with my old friends!

Nesting Carolina wrens

A few years ago I enclosed my front porch and built some cubbies to store my running shoes. It wasn't long after that the Carolina wrens discovered the cubbies and started building their nests tucked away in my shoes. This happened three years in a row, but the nests never had any eggs in them. While my shoes don't smell particularly nice, wrens don't have a well-developed sense of smell and don't seem to respond much to the scent of predators (and I don't think my shoes smell any worse than mink urine and feces: source). The behavior always struck me as odd - why go through all that trouble and put in such a big investment of energy to build a nest and not even use it? Here we look at some of the adaptive reasons a bird might build multiple nests.

That’s a lot of fur

A friend game me a challenge a bunch of years ago of finding any spot in the woods, sitting down, and not getting up until a I found a wild animal hair’s within arm’s reach. It was a great challenge, and on my first attempt took me about an hour to complete (it’s possible that the hair I found may have been one of my own). I often think about the ubiquity of lost hairs when out tracking animals in the woods, especially in the spring when some fur bearers molt. This weekend I came across a trail of deer tracks littered with fur and wondered just how hard this challenge is. So this week I’ll describe your odds of finding a deer hair in the woods and next week I’ll describe why deer hair is amazing.

Should You Pee When You’re Cold?

I felt cold yesterday while out at the Field School. It was a different kind of cold from today’s cold, wetter, less biting, but cold nonetheless. We were talking with the kids about ways to stay warm in the cold, and one of the suggestions that came up was that peeing would help you stay warm. This made me curious about the relationship between pee and cold weather and other creative ways I might be able to stay warm.

Orange Balls On Powerlines

Everytime I drive I-89, I notice those bright orange balls attached to the power lines that cross the interstate to the Bolton Falls Hydro Station (map). It seems an odd marker as there are plenty of other places where power lines cross the interstate or other major roads but aren’t adorned with these plastic orange ornaments. Not surprisingly, the visually obvious orange balls, called power line marker balls, are intended to make power lines visually obvious to pilots, particularly in places where airplanes and helicopters tend to fly at low altitudes (like around airports, mountain passes, deep valleys, or even on larger bodies of water where a float planes might land). The balls were invented in the early 1970s by Arkansas governor, Winthrop Rockefeller, who noticed their potential danger during the landing of a flight with Arkansas’ head of the Department of Aeronautics.

Wren Kitz album review

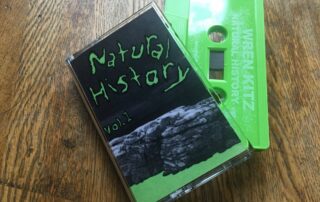

Identification is a most powerful skill. It illuminates, reveals, unlocking a secret world just beyond the edge of our tongue. There was magic in my early days as a naturalist, endless lost hours spent pouring over the intricacies of the various species of Atriplex that licked the salty scrub coast of California. As my ID skills developed I began to see patterns in the land, to appreciate the nuance of a slope's aspect, the soil's affinity for water, the lingering influence of land use on vegetative communities. I also came to understand that identification isn't a language, it isn't even the syntax, only the barest tracings of what the world is, a necessary foundation to reveal deeper truths about the world we inhabit. E.E. Cummings' words strolled through the arid chaparral with me: since feeling is first who pays any attention to the syntax of things will never wholly kiss you; I was again reminded of this poem while listening to Burlington musician Wren Kitz's new album, Natural History vol.1.

The Natural Community concept needs to go

As many Americans celebrated Thanksgiving last week, indigenous peoples from across the country and their allies gathered at Cole's Hill near Plymouth Rock for a National Day of Mourning. The first gathering was organized by Wamsutta (Frank James) in 1970 on the 350th anniversary of the Mayflower's landing and continues to this day. From this year's flyer: "many Native people do not celebrate the arrival of the Pilgrims & other European settlers. Thanksgiving Day is a reminder of the genocide of millions of Native people, the theft of Native lands and the erasure of Native cultures" (link). And it is the last point that has been gnawing at me as I wrap up my unit on natural communities in my natural history class.

UVM’s Rifle Range

A good mystery is a fine companion to carry with you through the years. It nags like a pair wet socks, a constant reminder of an itch that needs scratching, to not to let go of your curiosity. I've had just such an itch for about 15 years now. Recently, and sort of haphazardly I stumbled upon a satisfactory answer! It feels good, but also a bit like I've lost an old friend.