Feeding Sign From Yellow-bellied Sapsuckers

And if the sap is almost flowing that means that yellow-bellied sapsuckers will soon be arriving back in our forests (sapsuckers in the Pacific Northwest are followed soon after by hummingbirds: video, so we can expect those soon too). Well, sort of. As you can see in the image below, there are sightings of yellow-bellied sapsuckers in Vermont throughout the winter (though they’re far less abundant than they are in the spring when the sap is flowing).

Relative abundance of yellow-bellied sapsuckers in Vermont throughout the year (eBird.org)

So how do sapsuckers thrive in the winter when sap isn’t flowing?

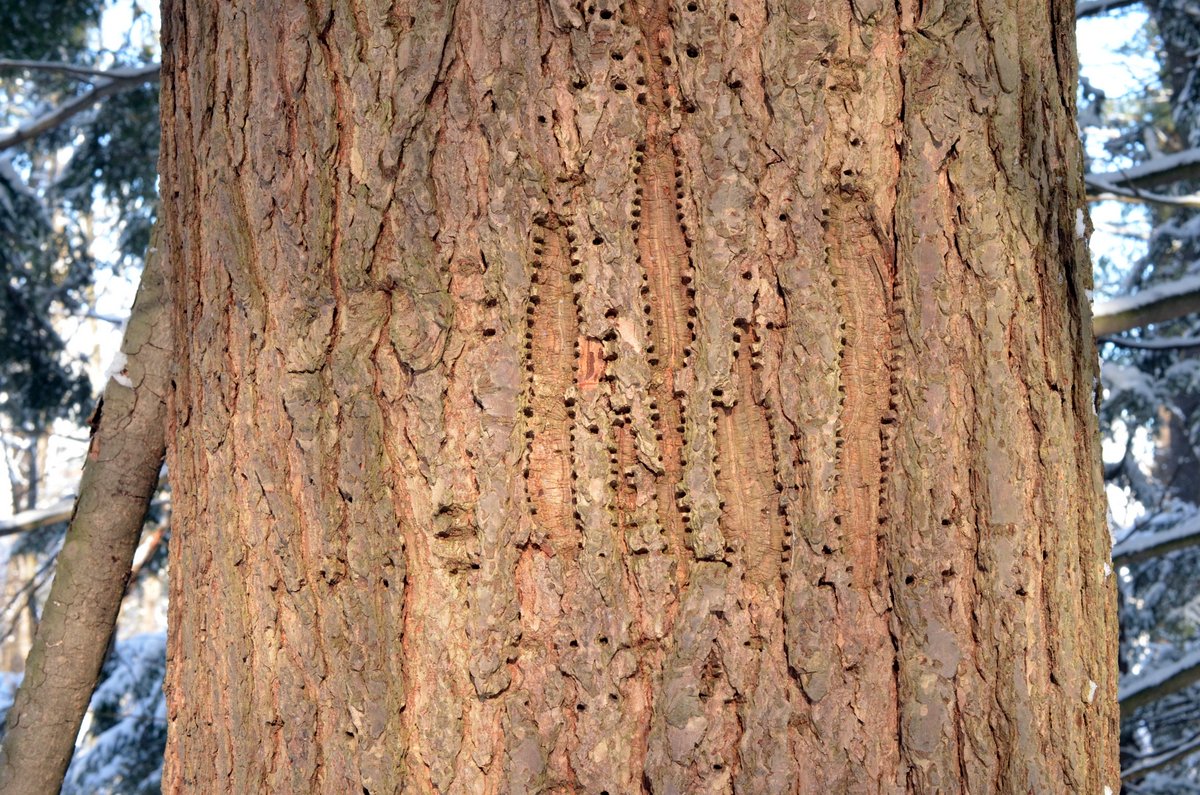

As much as I like to think ahead to the warmer months, I’m still relishing such the snowy winter we’ve been having. Yesterday morning I was wandering down along the Winooski River in search of basswood when I was struck by just how many trees had been pockmarked by sapsuckers. Of the 15 or so species of trees at Muddy Brook Park in South Burlington, seven of these that had scars on their trunks from sapsuckers feeding (American elm, hophornbeam, musclewood, silver maple, sugar maple, basswood, and hemlock – basswood, by far, was the most commonly selected species even though it wasn’t necessarily the most abundant tree). As their name implies, sapsuckers drill tap holes into the trunks of trees and then come back to lick up the sap that flows freely from the wounds (they also feed on insects attracted to the sap). These wounds quickly seal up and so a sapsucker must maintain the holes to keep the sap flowing.

When it comes to sap, they’re generalists, with a study from the mid-1900s finding that across their range, sapsuckers tapped 174 different species (source). They do tend to narrow the range of their diet during the breeding season, primarily to birches (source), but the number of species is likely much higher. Finding all those tap holes along the river got me thinking about just how a sapsucker can survive in the winter here in the northern part of its range.

Diet

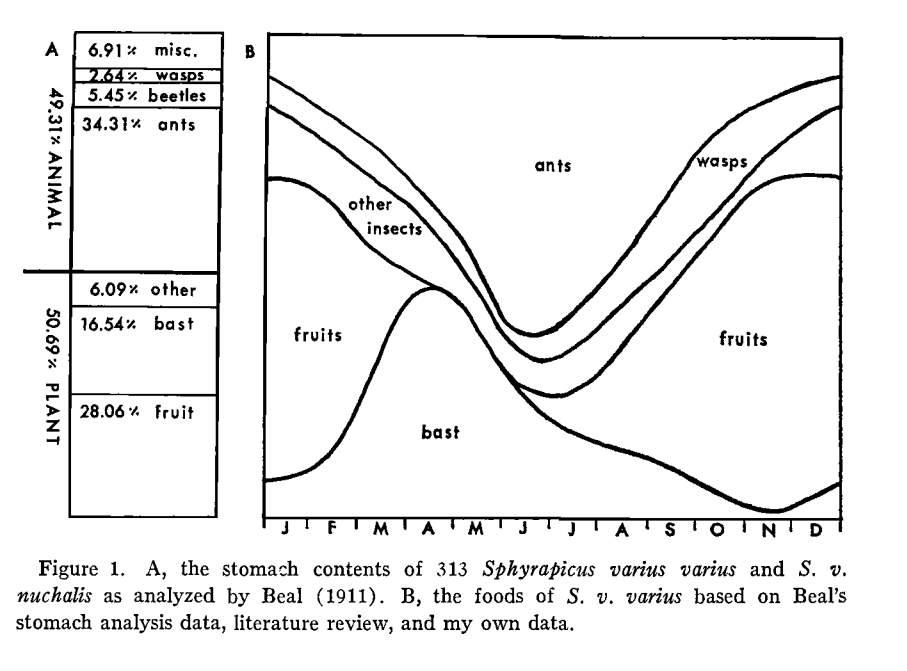

Because a sapsucker’s diet is skewed towards sap, particularly in the spring and summer, their seasonal range tends to follow the seasonality of sap flow. In the image above, you can see the fine hairs on their tongues are adapted to slurping up sap. But they are, in fact, more than one-trick ponies and branch out throughout the year to forage on insects, fruits, and bast to supplement their sappy diet (these supplements entirely supplant sap in the winter months).

From "Methods and annual sequence of foraging by the sapsucker" (source)

Diet

You may have heard the term bast in reference to bast fibers – those inner bark fibers that can be used to weave rope, baskets, bags, and rugs (I’ve used bast fibers from dogbane, milkweed, nettles, elm, and mulberry). To a botanists, bast refers the inner bark of a tree (you can find my detailed article on bark here). Inner bark is alive at maturity (unlike xylem, which makes up the wood of a tree), so it’s full of sugars, proteins, fats, and lots of other digestible material for animals. While most energy is stored down in the roots for safe keeping during the winter, sugars are an effective antifreeze agent and some sugars are stored in the inner bark of a trunk. Since inner bark is alive and metabolically active, having sugars stored in the bast also allows the tree trunk to stay active on warmer days during the winter. By pecking away at the trunk and eating the bast fibers, this sweet, living tissue can thus support a sapsucker through the winter months when the sap isn’t quite flowing.

Seasonal Preference

While sapsuckers may feed on a wide range of species, they do show preferences both seasonally and based on environmental conditions (source). Hemlocks, for example, were exploited primarily in April and again later in the summer after hardwood sap flow tapers. In drought years, hemlocks were preferred, but in wetter summers, hemlocks were avoided altogether. On the other hand, sapsuckers appear to be less than enthusiastic about red maple, but will spend more time tapping them in wetter years. This suggests that all things equal, hemlocks aren’t top of the menu for sapsuckers, but provide a critical resource during dry periods. I’ve seen hemlock damage extensively (a close third to the birches and basswood), but never on other conifers like white cedar or white pine.

Paper birch is a core component of their diet from the breeding season through the last preparations for migration (if they migrate). They’ll even defend these trees from other sapsuckers (and other saprovores like hummingbirds and even martens!!). I’ve never seen an aspen tapped, but of the 7 nests I’ve found over the years, all have been in aspens (either quaking or big-toothed)!!