This is part of a 5-part series on black-legged/deer ticks. Two disclaimers to start:

- There is a lot of conflicting information out there. I’ve tried to rely only on the most recent peer-reviewed scientific research rather than personal experience, anecdote, blogs, and other unreliable sources

- While I might be a Master of Science, I am certainly no doctor. Please, please, please do your own research, talk to your own experts, and be your own advocate!

Lyme Disease

Removal

Prevention is always the best medicine. Caught early enough, simply removing an attached tick is sufficient in preventing the transmission Lyme disease (which is caused by the spirochete bacteria, Borrelia burgdorferi). The most effective and safe way to remove ticks is to use tweezers to pull the tick off. Pinch the tick’s mouth-parts as near to the skin as possible and pull straight up. Most resource say not to twist as you pull as this can rip off the mouth parts, but the tick tweezers I bought said explicitly on the package to twist as you pull. Pulling straight up works fine and reduces the risk of ripping off the mouth parts. There’s conflicting information about how much you should care about leaving mouth-parts in. The CDC says you should try to remove the mouth-parts if they break off, but if you can’t then don’t worry as the skin will just heal around them (link). Other sources suggest they might cause itchiness or even an infection. In either case, the mouthparts alone will not transmit Lyme (link).

Epidemiology + disease transmission

Some sources state that the spirochete bacteria, Borrelia burgdorferi, is not passed on from the mother to the egg, but a survey of over 16,000 ticks found that a small percentage of larval ticks were indeed carriers (link). At roughly 50%, Vermont has one of the highest rates of deer ticks that are carriers of the disease (link). This unfortunately translates to particularly high infection rates in people (85.5 confirmed cases per 100,000 residents). Nymphs are the most common transmitters of Lyme because they’re smaller than adults and often go undetected for longer.

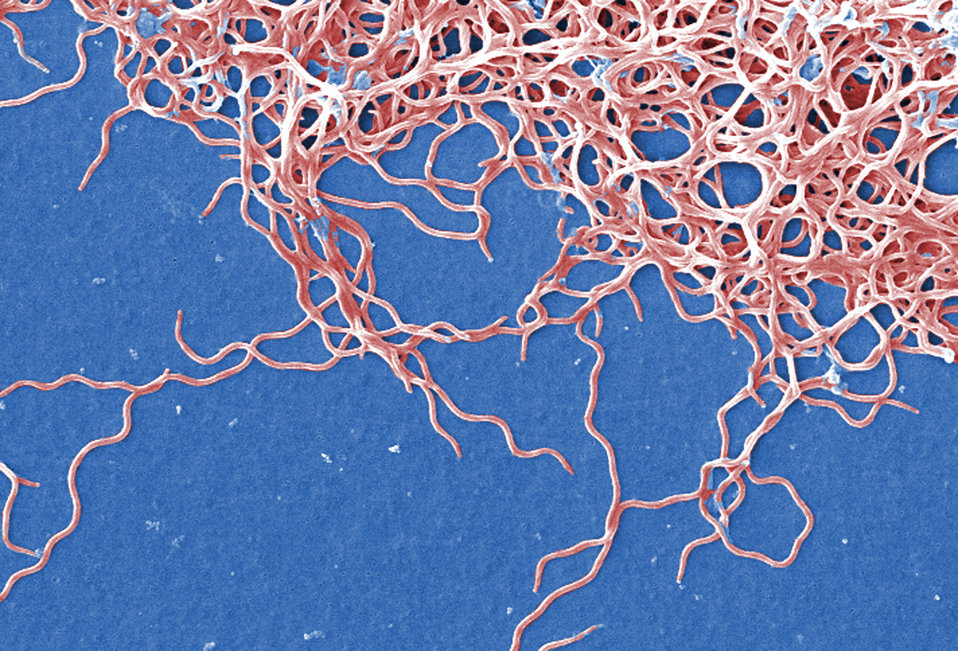

How the bacteria is transmitted

Many resources cite a 36-48 grace period after a tick attaches before it transmits the bacteria. It takes time for an attached tick to transmit the disease because a tick’s midgut secretes molecules that actually inhibit the movement of the bacteria from the midgut into the tick’s saliva. While trapped in the midgut, these non-motile (incapable of moving themselves) bacterial cells form networks that divide and surround epithelial cells in the midgut lining, Eventually these cell networks reach the base of the epithelium where they’re released from molecular suppression and again become motile. Once motile, small numbers of bacterial cells make their way into the tick’s saliva where they can be transmitted to a new host (link).

How long after a tick attaches until Lyme is spread?

But the 36-48 hour rule isn’t that simple or even reliable. There is no experimental evidence of a tick feeding on a single host transmitting Lyme disease within the first 24 hours of attachment. If a tick, however, prematurely detaches from another host (like a dog) and reattaches onto you, there is a very small chance that it can transmit the infection after 24 hours of being attached. But this is an extremely unlikely scenario. The longer the tick is attached, the more likely you are to contract Lyme (if the tick is a carrier). By 48 hours, the chance of transmission of Lyme is still only 10%. But after 72 hours, there’s a 70% chance of transmission. This paper (link) provides a great overview of this. Transmission rates also increased when multiple ticks fed together. Other diseases can be transmitted much quicker than Lyme. A new looming threat, Powassan Virus, can be transmitted in just 15 minutes.

Adult female deer ticks

Symptoms

The CDC describes both early (3-30 days after bite) and late (days to months after bite) signs and symptoms. But symptoms alone cannot be used to diagnose Lyme disease. A 2013 study concluded that “no clinical features, except erythema migrans [the red bullseye] or possibly bilateral facial nerve palsy – in the appropriate context – provide sufficient specificity or positive predictive value. Laboratory confirmation is essential except with erythema migrans” (link). And less than 70% of people that contract Lyme disease get this red bullseye rash (and oddly, this number is downtrending, link). The following symptoms are taken from the CDC page

Early symptoms

- Fever, chills, headache, fatigue, muscle and joint aches, and swollen lymph nodes

- Erythema migrans (EM) rash (photos of rashes)

Late symptoms

- Severe headaches and neck stiffness

- Additional EM rashes on other areas of the body

- Arthritis with severe joint pain and swelling, particularly the knees and other large joints.

- Facial palsy (loss of muscle tone or droop on one or both sides of the face)

- Intermittent pain in tendons, muscles, joints, and bones

- Heart palpitations or an irregular heart beat (Lyme carditis)

- Episodes of dizziness or shortness of breath

- Inflammation of the brain and spinal cord

- Nerve pain

- Shooting pains, numbness, or tingling in the hands or feet

- Problems with short-term memory

- Allergy to red meat (link)