Clearing the Land

Virtually all of Vermont’s landscape has been cleared at some point during the last 400 years. There’s maybe 1000-2000 acres of old growth forest remaining in the state, which represents ~.016% of the total land area in Vermont (even if you exclude the 4% of Vermont that is covered in water the number bumps up to just .17%). Early land clearing in the 17th and 18th century was largely for subsistence farms that cropped up throughout Vermont’s hills and valleys. Land clearing intensified with the arrival of the first merino sheep in 1812. As farms began exporting more and more wool (there were 6 sheep for every 1 person by about 1830), more forests fell to the axe. Railroads opened up markets down in Boston and beyond, and refrigerated rail cars soon made the dairy industry the primary agricultural pursuit in the state.

A few left for shade

For sheep and cow, shade goes a long way (it’s also not so bad for a farmer taking a respite from building a fence on a hot July day). And indeed a few trees were spared the blade, intentionally left behind to grow up and out into one of those large upside down octopi (or possibly just a hydrozoan) casting a thicket splash of shade on an otherwise open landscape.

But these farms weren’t to last long. About 10% of Vermont’s men went off to fight in the Civil War, and around the same time, completed rail lines connected the northeast to the superior agricultural lands out west. Cold, stony, hillside farms in the northeast were abandoned wholesale. Those open pastures that were kept open under the rapacious appetite and trampling feet of the grazers that sought shade under the wolf trees began to fill in with trees. With the grazers gone, the next generation grew spindly and straight up in tense competition to stake out a place in the canopy. These previously solitary wolf trees were soon engulfed in a forest of younger, straight trunked trees.

Finally, a definition

I’ve been using the terms wolf tree, shade tree, and pasture tree as though they were perfect synonyms. But there are a couple problems with this. First, shade and pasture trees (which can be used interchangeably) still exist and function in their intended capacity across the landscape today. Perhaps if the farms they’re growing on are left to the whims of nature rather than kept open, they’ll grow up to be wolf trees.

Wolf trees, on the other hand, are relics from the past, a tree that previously served a purpose, but has since been engulfed by a swarm of successionary trees. According to this article (though I couldn’t find the primary source), Eric Sloane, an American treasure (I highly encourage you to read all his books), suggested that for one of these large tentacled trees to be a wolf tree proper, it needs to be:

- >150 years old (this seems arbitrary and not super important, though does allude to the fact that it was around in a previous era when the land looked very very different)

- a different species from the younger trees growing around it (I don’t like this part of the definition. This feels more like a nod to forest succession, that primary succession trees likely would be different from the trees growing in the field prior to forest clearing. But this isn’t always the case – see below)

- a large tree growing by itself (or at least with few large neighbors growing immediately adjacent to it)

- left uncut for a specific reason (e.g. shade tree, witness tree, border tree)

So whether or not Sloane penned the list, I think the criteria are good enough to descrbe this woodland phenomenon.

Species of Wolf Trees

Wolf trees come in a variety of species, though white pine tends to be particularly common as wolf trees. Part of the reason is that white pine, which is also called old field pine, is particularly adept at growing in abandoned pastures. Its wind dispersed seeds scatter far and wide, but unlike the tiny seeds held in the winged fruits of birches, white pine seeds are relatively large. Each large seed stores enough energy to send its roots down through the duff and its shoots up into the “canopy” of grasses that make up a pasture.

The delicate young seedlings fall prey to the constant press of hooves wandering across the hillsides. But every now and then, nursed by an unpalatable juniper or thorny thicket of blackberries, a seedling might just make it high enough that it’s free of the plodding cow feet. After about 5 or so years, a white pine can start growing 1-2′ per year and will soon grow free of the threat of being trampled.

You can also get the same appearance if you remove all grazers from a pasture for a year or more. In the fallow years, the seed bank of white pines germinate and the seedlings compete in the early stages of abandonment. The cohort quickly becomes a dense, short monoculture of white pines. A new farmer comes in, cuts most of the white pines, leaves a few behind for shade trees, then abandons the farm a second time and voila, a white pine shade tree among a field of younger white pines.

Edge trees

Lest you think that every old tree with large lower branches was left as a shade tree, there are plenty of edge trees that line old farm edges. These trees, as with the maples below, were left as witness trees or posts for pinning up barbed wire. They’d still meet Eric Sloane’s definition as they were left behind for a specific reason, though just not to provide shape for cows or sheep.

You can also get the same appearance if you remove all grazers from a pasture for a year or more. In the fallow years, the seed bank of white pines germinate and the seedlings compete in the early stages of abandonment. The cohort quickly becomes a dense, short monoculture of white pines. A new farmer comes in, cuts most of the white pines, leaves a few behind for shade trees, then abandons the farm a second time and voila, a white pine shade tree among a field of younger white pines.

Wolf Tree Etymology

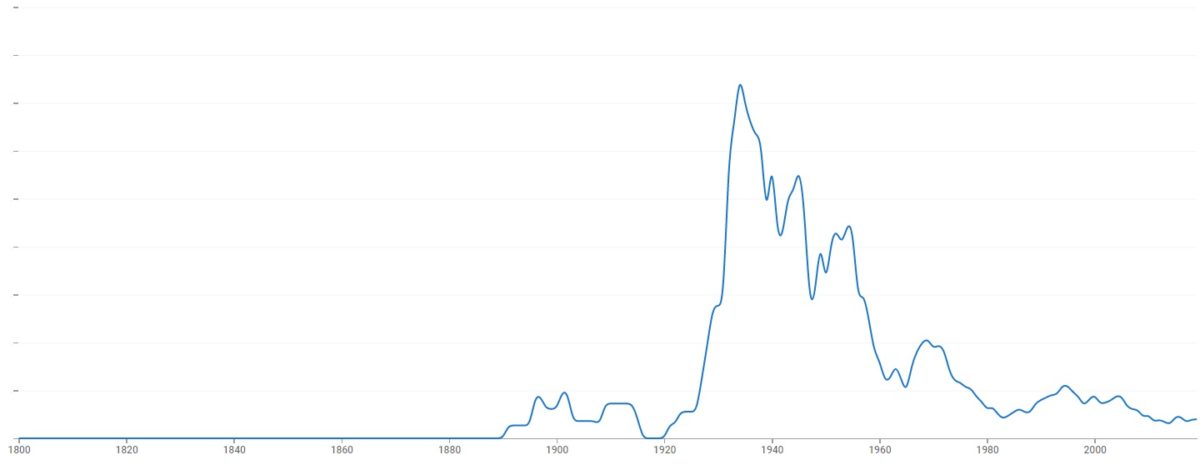

You can see in the chart above, that it’s not really until the 1930s that the phrase “wolf tree” comes to prominence. This makes sense, because most of these wolf trees would not have been swallowed up by our returning forests until the early 1910s, nearly 50 years after the Civil War and widespread farm abandonment. But still, why a wolf? The phrase always struck me as slightly odd. It reminded me of some anachronistic notion of a lone wolf hunting through the pastures, vilified by farmers. It made me think also of an alpha wolf, leading the charge, as these lone trees so too lead the charge from a pasture back to a forest.

The returning forests brought back a logging industry. And these loggers weren’t so thrilled with these giant, gnarly, hole-ridden trees. In a 2011 article in Northern Woodlands, Michael Gaige wrote: “These early foresters suggested that the wide-spreading, old trees were preying on forest resources and, like a wolf, should be culled to make way for merchantable timber. Though no wolves roamed the landscape then, the idea of wolves still haunted people and ran into their management metaphors” (source). Another article, entitled “Woodman, Spare that ‘Wolf” Tree”, extolled the virtues of wolf trees, a case that was apparently necessary to make as virtually all foresters and loggers saw the wolf tree as “avaricious,” “a worthless space filler,” and “forest ulcer.”