Life history of crayfish

The group of organisms that collective make up the crayfish are split into three families: Astacidae, Cambaridae, and Parastacidae. All of the crayfish found in the eastern part of the country belong to the family Cambaridae. In the past two centuries, crayfish have been moved all around the globe as bait, food, and pets. In understanding the role native crayfish play in their ecosystems and the effects introduced species have on their new environments, it’s critical to first understand crayfish ecology in general. There are certainly differences in the details across species lines, but the broad strokes of their life histories are quite similar. The following generalizations are written with crayfish of the northeast in mind, but generally apply to crayfish in other regions.

Habits

Most crayfish in the northeast are referred to as secondary burrowers. The ecological grouping describes crayfish who spend most of their lives in a variety of freshwater habitats but dig burrows to escape desiccation during the dry parts of summer and freezer in the cold months of winter. These crayfish tend to be in shallower water (less than 10′ deep) where the substrate has plenty of rocks and logs to provide cover from predators. Crayfish are more common in water with lower sediment load and rocky or gravelly substrates, the spiny-cheek crayfish is a notable exception. There are also primary burrowers (like the Devil’s crayfish) that live primarily in burrows excavated into terrestrial environments, typically down into the water table. Tertiary burrowers dig burrows to escape drought or freezing only in extreme situations, and these burrows are typically just shallow depressions excavated beneath rocks or logs.

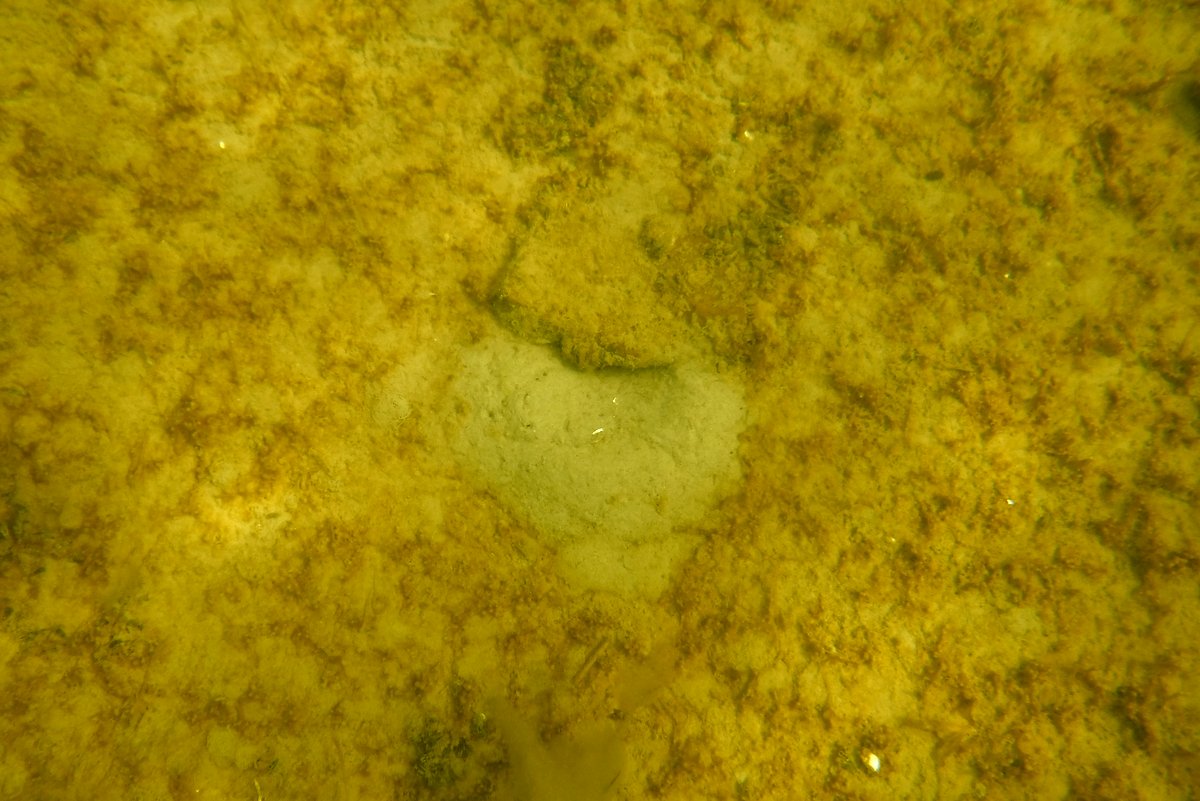

FINDING BURROWS: Particularly in shallow edges of lakes and ponds it can be quite easy to find crayfish burrows (especially those of the Faxonius genus). Because they excavate out materials, the entrance to burrows often contrast sharply with the surrounding substrate. Some larger species eat zebra mussels (see this source for more), and the entrance to their burrows is littered with shells.

Mating

Males and females are sexually dimorphoic; read this page for more on the differences between the two sexes. Breeding season typically begins in the late summer and into fall. At maturity, males have two forms. Males have a special reproductive form (F1) that they molt into in advance of the breeding season, typically around July or August. In F1 males, the ischia (3rd segment) of their second set of walking legs have pronounced hooks used for grasping onto the females during mating. After molting into F1, their gonopods (the male reproductive structures) become sclerotized, or structurally stronger.

Females initiate mating by urinating in the water to signal sexual receptivity. Detecting the chemical signals, males respond by approaching the female, at which point the females become aggressive (source). The pair wrestles, with the larger female typically having the upper hand. If the female eventually relents, the male will mount the female. They remain joined for 30-90 minutes, during which the male will use his gonopods to deposit a spermatophore (a sperm packet) on the female’s annulus ventralis, the seminal receptacle midway between the abdomen and cephalothorax. The annulis ventralis is then coated by a waxy sperm plug released by the male.

A single male may mate with several females. Females as well will mate with multiple males (and, at least in the spiny-cheek crayfish, show a preference towards virgin males: source), but typically retain the spermatophore from just a single male. Males will attempt to remove the spermatophore from a female who has already mated. In most species of crayfish, the male will die shortly after mating.

Egg laying & care for young

Sperm is stored through the winter either on the annulus ventralis or inside of a spermatheca. In the spring, as temperatures warm and waterways thaw, the female readies herself to lay eggs by grooming her abdomen, cleaning it of any debris or algal growth that may have accumulated. She’ll then release a sticky substance, called glair, from glands at the base of her abdomen, just behind the telson, coating her abdomen and tail fan in the substance. Glair simultaneously breaks down the sperm plug, which releases the sperm just as the female releases her eggs. She curls her abdomen under her body as she deposits her eggs over 30 minutes (up to 4 hours). Eggs are covered in a sticky membrane and attached to the swimmerets lining the abdomen by a fiber made from glair. The eggs stay attached to the female while they incubate over the next few weeks.

Females carrying eggs are called “in berry.” They remain relatively inactive while incubating their eggs, hiding in secluded areas typically standing with their tail curled under their body to protect the eggs and prevent them from detaching. She’ll unclear her tail occasionally to clean the eggs. The eggs hatch after several weeks. A young crayfish will molt within the first 48 hours and again a week later, all the while firmly clamping down to the female with its claws. After the third molt, the young crayfish will release its grip and is finally detached from its mother. The young will remain close to the female for another week or so – the female releases a hormone during this period that the young use as a beacon to guide them back to safety.

Molting & Growth

Like all arthropods, crayfish have rigid exoskeletons. In order to get bigger, they must shed their exoskeletons, replacing the old one with a new, larger exoskeleton (called ecdysis). Juveniles devote most of their resources towards growth, and must molt frequently (8 to 12 times in their first year) to accommodate their rapid increase in size. There are four stages to each molt:

- Premolt: The exoskeleton is an expensive thing to waste. Before a molt, the exoskeleton is soften as the crayfish retrieves calcium and phosphates from the shell. The nutrients are stored in the foregut and used to forge the next exoskeleton, which begins to develop beneath the old one.

- Molt: The exoskeleton splits in a seam between the thorax and abdomen. The crayfish slides out of the weakened exoskeleton (video).

- Postmolt: The new exoskeleton is soft and the crayfish is in an incredible vulnerable period, so it will remain hidden. Crayfish reinforce the feeding parts with calcium stored in its gastroliths (in the foregut). It begins to feed again, and calcium extracted from its food goes to reinforcing the rest of its exoskeleton

- Intermolt: The dominant stage of a crayfish’s life is spent in this phase, the period between molts.

Feeding

Crayfish are commonly described as opportunistic omnivores. While they certainly eat algae, detritus, and plant material, most get the bulk of their food by eating carrion, fish eggs, tadpoles, fish, salamanders, snails, insects, mussels, and other animals. Most studies of crayfish diet look at their stomach contents, which are biased towards plant materials which is digested more slowly. Additionally, they grind their food down before consuming, so it can be difficult to discern what exactly has been eaten by the crayfish. Juveniles are typically obligate filter feeders while adults are facultative filter feeders (source). Crayfish are primarily out foraging, grazing, collecting, and feeding at night, though North American crayfish tend to be more diurnal than their European counterparts.

Winter

Activity during the winter slows drastically. Crayfish are not true hibernators, but their actiivity levels slow dramatically during the winter. By late fall, sexually mature males have mostly died after mating. The remaining crayfish seek deeper water or dig burrows where they’ll pass the cold dark months slowly burning through energy stores and eating minimal amounts of food.

Identifying Crayfish

For most people, crayfish tend to all look like little brown lobsters. But once you learn what to look for, ID seems not just vaguely possibly, but actually easy and, dare I say, fun! It’s often easier to sex a crayfish than to identify a species, so here we’ll cover both species and sex identification.